Infarct related artery only versus complete revascularization in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and multi vessel disease: a meta-analysis

Introduction

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) to establish TIMI 3 blood flow to culprit vessel obstruction and achieve myocardial reperfusion in a timely manner is the accepted standard of the treatment of patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) (1). About 40–65% of the patients who present with STEMI are found to have co-existing disease in non-infarct related arteries (2,3). The 2015 focused update of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association (ACCF/AHA) and 2014 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines for patients with STEMI recommend PCI of the non-culprit artery at the time of primary PCI as a class IIb (weak) recommendation if the patient is hemodynamically stable (4,5).

Both of these guidelines permit PCI of the non-culprit artery at a time separate from primary PCI for symptoms, or for ischemia on noninvasive testing. The appropriate use criteria for coronary revascularization however, do not recommend revascularization of the non-culprit artery during index hospitalization (6). The recommendation for concurrent treatment of non-infarct vessels with significant stenosis to achieve complete revascularization during the initial procedure is reserved for patients with hemodynamic compromise (7). Nonetheless, the optimal management of multi-vessel disease in this setting remains controversial.

The recent DANAMI-3-PRIMUTLI trial studied the clinical outcome of patients comparing fractional flow reserve guided complete revascularization with infarct related artery (IRA) only PCI and found that the composite of (all-cause mortality, nonfatal re-infarction, repeat revascularization) was significantly lower in the complete revascularization group mainly driven by a reduction in repeat revascularization rates (8). Given the absence of definitive clinical trial data regarding the best approach for non-culprit revascularization at the time of STEMI we conducted a meta-analysis to check concordance with current guidelines and evaluate an optimal treatment strategy.

Methods

Eligibility criteria and quality assessment

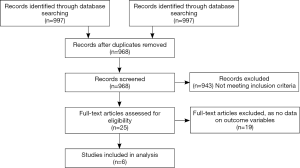

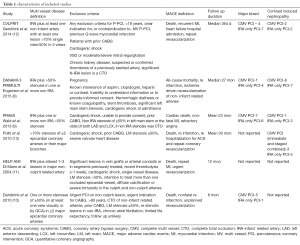

Randomized controlled trials available as of 2/29/16 which compared outcomes between complete revascularization (at the time of primary PCI or staged) and IRA only revascularization, were included (8-13). All the trials had major adverse cardiac events (MACE), nonfatal re-infarction, repeat revascularization and cardiovascular mortality as outcomes. The search was conducted in PUBMED, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register for controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and MEDLINE databases with the algorithm shown in Figure 1. The meta-analysis was performed as per recommendations from Cochrane Collaboration and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses PRISMA statement (14-16). In addition, we searched the major cardiovascular conference proceedings, bibliographies of original trials, meta-analyses and review articles. The search terms used were “complete revascularization”, “multi-vessel revascularization”, “culprit only revascularization”, “target vessel revascularization”, “preventive angioplasty”, “non-culprit lesion”, “ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction” and “randomized controlled trial”. Only human studies were included. Citations were screened at the abstract level and retrieved as full reports if they fulfilled the inclusion criteria.

Studies which met the following inclusion criteria were included:

- Studies with STEMI patients;

- Randomized trials comparing complete versus culprit only revascularization;

- Data for outcome variables of interest.

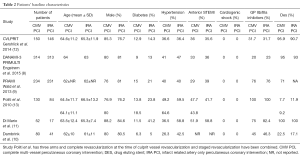

The study of Politi et al. had three randomized intervention arms: culprit only revascularization, complete revascularization performed simultaneously at the time of culprit artery PCI, complete revascularization performed as a staged revascularization (13). For this study, the latter two arms were combined into one complete revascularization arm. Data were extracted after assessing the trial eligibility by all the authors and disagreements were resolved by consensus. The risk of bias for randomized studies was assessed using the components suggested by the Cochrane Collaboration, which are random sequence generation, random allocation; allocation concealment; blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors; incomplete outcome data; selective outcome reporting and other sources of bias (17). The quality of studies was assessed by the Jadad Score, which ranges from 0–5 (18). Two studies had a Jadad score of 2 (8,11). One study had a score of 3 (13). Three studies had a score of 4 (9,10,12).

Outcomes

Both efficacy and safety outcomes were evaluated. Efficacy outcomes included MACE (composite of death, recurrent myocardial infarction and repeat revascularization), cardiovascular mortality, recurrent myocardial infarction (MI; non-fatal re-infarction), repeat revascularization and all-cause mortality. The safety outcomes assessed were major bleed rates and contrast induced nephropathy (CIN).

Statistical analysis

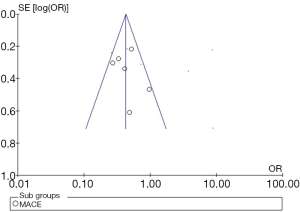

The meta-analysis was performed using Revman version 5.3 (Cochrane, Oxford, UK). The random effects pooled risk ratios (RRs) were calculated using DerSimonian and Laird method. Heterogeneity is proportion of total variation observed between trials which is due to differences between trials rather than sampling error, it was assessed using Cochrane’s Q statistic and I2 values (19). The I2 <25% was considered low and I2 >75% was considered high. Publication bias was assessed using a funnel plot, which was constructed for the primary end point MACE. The SE (standard error) of the log OR was plotted against OR (Figure 2) (20).

Results

A total of 997 articles were identified by literature search, out of which 25 full text articles were retrieved and reviewed. Six randomized trials met the inclusion criteria yielding 1,792 patients. A total of 832 patients had culprit vessel PCI only. Among the 960 patients who underwent complete revascularization, 448/960 (46.7%) underwent it at the time of index procedure. All studies compared complete MV-PCI (multi-vessel) versus infarct related artery (IRA) only PCI. Additional interventions in the IRA only PCI group were allowed in all included trials. Significant stenosis in non IRA vessels was defined as >70% in two trials (12,13). None of the trials included patients with cardiogenic shock and left main stenosis ≥50%. Three trials excluded patients with chronic total occlusion (CTO) in non IRA vessels (9,10,12). Four trials excluded patients who had prior CABG (9,10,12,13). Drug eluting stents were used in the majority of patients in four trials (8,9,11,12). Follow-up across included trials ranged from six months to 2.5 years. The study characteristics and patients’ baseline characteristics are summarized in Tables 1,2, respectively.

Full table

Full table

Major adverse cardiovascular events

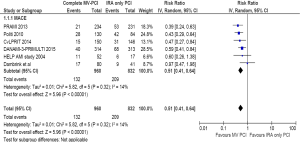

The MACE definitions are slightly different across studies (Table 1). MACE typically was a composite (e.g., death, nonfatal re-infarction, repeat revascularization) but incorporated re-hospitalization for acute coronary syndrome (13), refractory angina (9) and heart failure hospitalization (12) in isolated studies. All six studies (N=1,792) contributed to the analysis. The incidence of MACE was 13.8% in complete revascularization group versus 25.1% in the IRA only PCI group (RR =0.51; 95% CI: 0.41–0.64, P<0.00001) (Figure 3). Heterogeneity for this analysis was low (I2=14%).

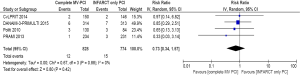

Cardiovascular mortality

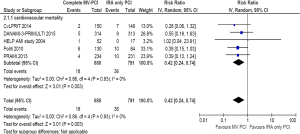

Five trials (N=1,671) contributed to the analysis. The incidence of cardiovascular mortality was 2.0% in the complete revascularization group versus 4.6% in the IRA only PCI group (RR =0.42; 95% CI: 0.24–0.74, P=0.003) (Figure 4). Heterogeneity was very low (I2=0%).

All-cause mortality

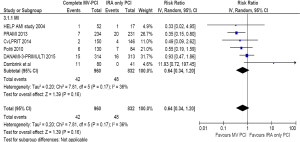

Six trials (N=1,792) contributed to the analysis. The incidence of all-cause mortality was 4.6% in complete revascularization group versus 6.0% in the IRA only PCI group, (RR =0.75; 95% CI: 0.49–1.14, P=0.17) (Figure 5). Heterogeneity was low (I2=7%).

Nonfatal re-infarction

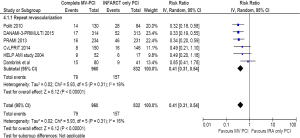

Six trials (N=1,792) contributed to the analysis. The incidence of nonfatal re-infarction was 4.4% in complete revascularization group versus 5.8% in the IRA only PCI group, (RR =0.64, 95% CI: 0.34–1.20, P=0.16) (Figure 6). There was moderate heterogeneity I2=36%, which appeared to be driven by the data from the Dambrink et al. trial (10). Exclusion of this trial resulted in complete revascularization decreasing the incidence of nonfatal re-infarction by 41% compared to the IRA only PCI, (RR =0.59, 95% CI: 0.38–0.93, P=0.02).

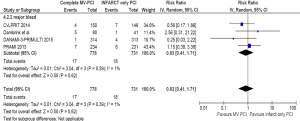

Repeat revascularization

Six trials (N=1,792) contributed to the analysis. The incidence of repeat revascularization was 8.2% in complete revascularization group versus 18.9% in IRA only PCI group, (RR =0.41, 95% CI: 0.31–0.54, P<0.00001). The heterogeneity was low (I2=16%) (Figure 7).

Safety outcomes

The incidence of CIN was comparable in both cohorts despite a higher mean contrast volume in the complete revascularization group (RR =0.73; 95% CI: 0.34–1.57, P=0.42) (Figure 8). Four trials (N=1,602) contributed to this analysis. Major bleed rate was also comparable in both groups (RR =0.83; CI: 0.41–1.71, P=0.62) (Figure 9).

Discussion

The result of the present meta-analysis with data derived from randomized controlled trials demonstrates that the complete multi-vessel PCI in the setting of STEMI is safe and feasible. The main findings are that complete multi-vessel PCI (MV-PCI) as compared to IRA only PCI: (I) is associated with significant reduction (49%) in composite primary endpoint MACE. The benefit is mainly derived from significant reduction (59%) in revascularization rates; (II) is associated with significant reduction (58%) in cardiovascular mortality rates. The other outcomes of all-cause mortality, nonfatal re-infarction rates were numerically lower in complete revascularization group but there was no statistically significant reduction.

Various studies suggest that multi-vessel disease is common in patients with STEMI (40–65%). In this setting presence of significant non-culprit lesions is associated with poor outcomes. The basis of current ACCF/AHA guidelines are concerns regarding prolonged intervention, increased radiation dose, increased contrast volumes with associated risk of CIN, need for increased doses of anticoagulants due to pro thrombotic and pro inflammatory environment, impaired assessment of non-culprit lesions and overestimation of their severity due to hyper-adrenergic state and associated vasoconstriction. The findings of the PRAMI trial had opened up this question for further discussion (9). This trial data showed that there was a 65% reduction in MACE (composite cardiac death, nonfatal MI or refractory angina) over 23 months of follow-up in favor of complete revascularization (P<0.001) and was terminated early based on recommendations from the data safety and monitoring board due to a significant difference in the primary outcome between the groups.

The CvLPRIT trial enrolled 296 patients who were randomized to the complete revascularization or IRA only revascularization groups (12). The primary endpoint was a composite of all-cause death, recurrent myocardial infarction, heart failure and ischemia driven revascularization. There was a 55% reduction in the primary end point at 12 months for the complete revascularization group. The safety outcomes were comparable between the two groups. The trial was not powered to detect differences in incidence of death and MI.

Recently, DANAMI-3-PRIMULTI trial enrolled 627 patients and randomized to complete PCI guided by FFR values group and IRA only PCI group (8). The primary outcome was a composite of all-cause mortality, non-fatal re-infarction and ischemia driven revascularization of non-infarct related arteries. There was a 44% reduction of the primary end point and a 69% reduction in revascularization in the complete revascularization group.

The data on pathophysiology in multi-vessel disease suggests that they are at increased risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality as compared to subjects with single vessel disease. Multiple complex coronary plaques are indicative of advanced coronary disease, other than the ruptured plaque itself. Studies have hypothesized that in patients with STEMI, pathophysiological alterations like endothelial dysfunction, pro-inflammatory and pro-thrombotic state are more generalized in the entire coronary tree rather than the culprit vessel alone (21). Also, a pro-inflammatory state is induced by STEMI, suggested by elevated serum levels of inflammatory markers (e.g., C-reactive protein) and pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., interleukin-6) found in about 45% of patients even at 6 months of follow up (21). These data indicate that the inflammatory processes are active for a long time after the acute coronary event and can have an influence on the stability of complex non-culprit lesions. This pro-inflammatory state might ultimately lead to premature acute coronary events by destabilizing the lesions in the non-culprit vessels. We believe that this pathophysiological mechanism might be the basis of the results of our study.

Limitations of our study include minor variability of inclusion/exclusion criteria and variability in follow-up duration in the trials included in the analysis. Many of the studies excluded patients with CTO and prior CABG and thus the results are applicable to a select group of patients enrolled in the trials. The open labeled nature of the trials and the fact that randomization was done after investigators had information about coronary anatomy could be a source of selection bias. Some of the studies were not powered to detect differences in death and myocardial infarction rates. This study compared the complete vs. IRA only PCI but does not address the question of timing whether immediate or staged. Our analysis does not answer the question of effectiveness of complete revascularization in reducing the outcomes of all-cause mortality and nonfatal re-infarction. The ongoing Complete vs. Culprit-only revascularization to Treat Multi-vessel disease After Primary PCI for STEMI (COMPLETE) multicenter trial is anticipated to enroll about 3,900 patients from all over the world and is powered for the outcomes of death and MI. It is also expected to address the risk of major bleeding between the two groups.

Conclusions

Complete revascularization (immediate and staged) is associated with a significant reduction in MACE mainly driven by a significant reduction in repeat revascularization rates and cardiac death rates when compared with IRA only revascularization in patients with STEMI and multi- vessel disease. There was no significant difference in all-cause mortality and non-fatal re- infarction between the two groups. We concur with the current guideline recommendations of ACCF/AHA. Larger trials are needed to determine if complete revascularization decreases death or non-fatal myocardial infarction.

Acknowledgements

Authors are thankful to Tracy J. Koehler, PhD and Alan T. Davis, PhD for reviewing statistical analysis.

Footnote

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- O'Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2013;127:529-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sorajja P, Gersh BJ, Cox DA, et al. Impact of multivessel disease on reperfusion success and clinical outcomes in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention for acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 2007;28:1709-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goldstein JA, Demetriou D, Grines CL, et al. Multiple complex coronary plaques in patients with acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2000;343:915-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, et al. 2015 ACC/AHA/SCAI Focused Update on Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Patients With ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: An Update of the 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention and the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;67:1235-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Windecker S, Kolh P, Alfonso F, et al. 2014 ESC/EACTS guidelines on myocardial revascularization. EuroIntervention 2015;10:1024-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Patel MR, Dehmer GJ, Hirshfeld JW, et al. ACCF/SCAI/STS/AATS/AHA/ASNC/HFSA/SCCT 2012 Appropriate use criteria for coronary revascularization focused update: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Thoracic Surgeons, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American Heart Association, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, and the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;59:857-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Smith SC Jr, Feldman TE, Hirshfeld JW Jr, et al. ACC/AHA/SCAI 2005 Guideline Update for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention-Summary Article: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (ACC/AHA/SCAI Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention). J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:216-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Engstrøm T, Kelbæk H, Helqvist S, et al. Complete revascularisation versus treatment of the culprit lesion only in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and multivessel disease (DANAMI-3—PRIMULTI): an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015;386:665-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wald DS, Morris JK, Wald NJ, et al. Randomized trial of preventive angioplasty in myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1115-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dambrink JH, Debrauwere JP, van 't Hof AW, et al. Non-culprit lesions detected during primary PCI: treat invasively or follow the guidelines? EuroIntervention 2010;5:968-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Di Mario C, Mara S, Flavio A, et al. Single vs multivessel treatment during primary angioplasty: results of the multicentre randomised HEpacoat for cuLPrit or multivessel stenting for Acute Myocardial Infarction (HELP AMI) Study. Int J Cardiovasc Intervent 2004;6:128-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gershlick AH, Khan JN, Kelly DJ, et al. Randomized trial of complete versus lesion-only revascularization in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention for STEMI and multivessel disease: the CvLPRIT trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;65:963-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Politi L, Sgura F, Rossi R, et al. A randomised trial of target-vessel versus multi-vessel revascularisation in ST-elevation myocardial infarction: major adverse cardiac events during long-term follow-up. Heart 2010;96:662-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available online: http://handbook.cochrane.org/

- Moher D, Cook DJ, Eastwood S, et al. Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: the QUOROM statement. Quality of Reporting of Meta-analyses. Lancet 1999;354:1896-900. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:1006-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Turner L, Boutron I, Hróbjartsson A, et al. The evolution of assessing bias in Cochrane systematic reviews of interventions: celebrating methodological contributions of the Cochrane Collaboration. Syst Rev 2013;2:79. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials 1996;17:1-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sterne JA, Egger M. Funnel plots for detecting bias in meta-analysis: guidelines on choice of axis. J Clin Epidemiol 2001;54:1046-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Buffon A, Biasucci LM, Liuzzo G, et al. Widespread coronary inflammation in unstable angina. N Engl J Med 2002;347:5-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]