The image of a disabled person in art through the ages

Throughout the entire history of human development, there have been pathologies leading to persistent, irreversible changes in the human body, making a person fully or partially dependent on others. Civilization has made many benefits accessible to healthy people, while simultaneously creating barriers for the disabled. In recent decades, society’s attitude towards disabled has changed, and we are making maximum efforts to break potential barriers, making life for people with disabilities more comfortable and complete. Currently, for physicians, the common visualization of both external (1) and internal (2) manifestations of chronic diseases are images in medical articles, however, if we broaden our perspective, we find representations of disabled people in various forms of art. Studying objects of art, including paintings, allows us to trace how society’s attitude towards people with persistent health disorders has changed: monster, freak, object of wonder and pity, part of the crowd, spirit of the nation…

In ancient Sparta, where the cult of the human body, its strength, and endurance was professed, any deviations in body structure were perceived extremely negatively, up to the point of infanticide. The first mentions of disabled people are reflected in the legislative documents of the ancient world, where they were equated to slaves and animals. In ancient Rome, children with congenital deformities were put to death, but deaf and blind people who were slave owners possessed some rights, nevertheless, they were forbidden from participating in social life and were not considered fully competent. This corresponding attitude is reflected through idealized human bodies captured in ancient sculptures such as The Doryphoros of Polykleitos, Laocoön Group (3).

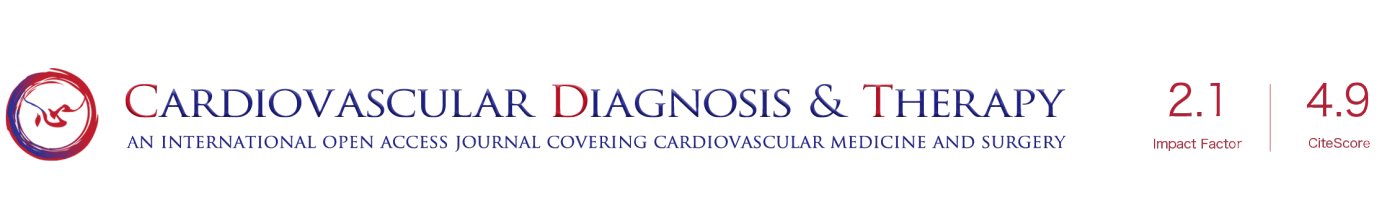

In ancient Egypt, however, the attitude towards disabled people was completely different—moral writings taught respect for such people, and they were often employed in the sphere of art and as assistants in these tasks.

The oldest known depiction of a blind musician—a mural of a blind musician playing a harp, from the tomb of the ancient Egyptian scribe called Nakht. This masterpiece is over 3,000 years old (Figure 1).

The perception of disabled people in the Middle Ages changed significantly. Christianity played a leading role in this, preaching mercy. The poor and the crippled were depicted as people deserving help and compassion, meaning they were assigned the role of dependent, weak, and helpless. However, alongside this, prejudices and superstitions towards the disabled began to grow in society (Figure 2). It was claimed that deviations in a person’s development were manifestations of an Evil Spirit. When society is overcome by fear, it starts to blame the disabled, women, immigrants—anyone who is different and easily turned into an exile.

During the Renaissance, people’s views on the very purpose and meaning of human life and nature changed. Here we saw the formation of new philosophical systems, as well as an increased faith in human intellect and capabilities. Assertions emerged that it was necessary not only to give alms and create shelters for the disabled but also to provide conditions for their education. The church played an important role in this process. In religious paintings, we find many examples depicting the healing of lepers and cripples through the power of faith.

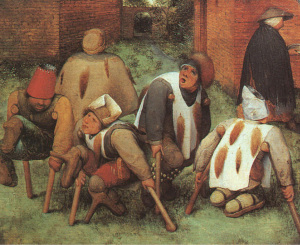

A prominent reflection of society’s increased interest in bodily anomalies is seen in many works from the 16th and 17th centuries, such as Hiëronymus Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights and Quinten Massys’s An Old Woman (also known as The Ugly Duchess). However, such works often depict ugliness and anomalies as human sin, reflecting the idea that external appearance corresponds to the inner world, again making people with disabilities social outcasts. Over time, the authority of the church in Europe diminished, and many of the charitable services it provided ceased to exist. The poor and unfortunate became homeless during the rapid growth of urban centers. For example, in Paris in the early 1500s, about a third of the population resorted to begging as a mean of survival. Many people with disabilities survived by begging (Figure 3).

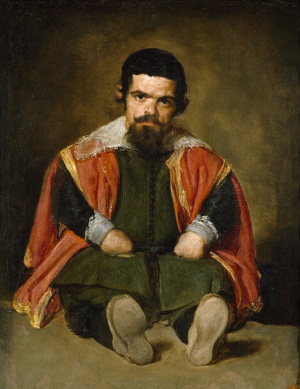

At the same time, people who looked differently or acted differently mentally were often regarded as popular pets at the royal court. Dwarfs, for example, were depicted in the works of the Spanish Baroque artist Diego Velázquez (Figure 4) (4). However, it should be noted that before Velázquez, they were often portrayed parodically: with the master’s hand on their head, with pets, or with each other, such as in Alonso Sánchez Coello’s Infanta Isabel Clara Eugenia with the Dwarf, Magdalena Ruiz.

At the same time, there are works depicting people with visible illnesses in a respectful, sympathetic manner, such as Jusepe de Ribera’s The Clubfoot (5).

During the Enlightenment, the development of social assistance policies for people with disabilities occurred, as well as the emergence of the idea of equality for all people. Due to this, humanistic teachings appeared, influencing the main directions of social support for people with disabilities. Increasingly, visual art features works where we sense the author’s respectful attitude towards people with disabilities (6).

Enlightenment art fosters concepts such as goodness, justice, humanity, optimism, faith in progress, the triumph of reason, and the harmony and beauty of existence.

In Francisco Goya’s painting Beggars Who Get about on Their Own in Bordeaux (Figure 5), the protagonist looks dirty and disheveled, yet actively participates in the social world. Even the title of the work emphasizes his mobility and independence.

In the painting Man with Delusions of Military Command by Jean Louis Théodore Géricault, the protagonist, who suffers from a mental illness, does not evoke feelings of rejection or pity (Figure 6).

Additionally, artists highlight the inhuman treatment of sick people by society, as seen in Francisco Goya’s The Madhouse, which can be interpreted as a critique of psychiatric hospitals of that time and the cruel treatment of mentally ill people.

In the 19th century, the medical model of disability emerged, which classified disability as an impairment, something wrong with the body. With the development of modern scientific medicine and the professionalism of this discipline, 19th-century doctors developed the concepts of disease and injury to denote deviations from normal body functioning. Disabled people became patients in need of treatment. By defining people by their disabilities rather than their human qualities, the medical model promoted segregation and dependence on professional help.

The particular interest, especially for physicians, shows a series of paintings created over several decades by Chinese artist Lam Qua. He created medical portraits of patients undergoing treatment by Peter Parker, a medical missionary from the United States. These works meticulously depict the patients’ physical defects, tumors, and deformities, yet this artistic precision does not conceal the artist’s compassion for his models (7,8).

The large-scale military conflicts of the twentieth century were reflected in many works where the protagonists were people with disfigured bodies and souls, such as Otto Dix’s War Cripples (1920) or Sergey Koltsov’s Victory Parade of the Disabled in Paris, November 11, 1928 (1932). The second half of the 20th century is characterized by the use of the image of the disabled as a source of motivation and stories of overcoming life’s difficulties. An example of this is Ubermensch by Jake and Dinos Chapman: a grand 12-meter-high sculpture depicting Stephen Hawking, balancing over an abyss in his wheelchair at the top of a cliff. In feature films, heroes with disabilities are often depicted courageously fighting with problems and then they heal. It can be said that positive discrimination arises—ordinary achievements of a person with a disability are greatly exaggerated, forgetting about the concept of equality, for example, this is Marc Quinn’s famous work Alison Lapper Pregnant (Figure 7). The real-life prototype, Alison Lapper, was born without arms and with disproportionate legs but managed to become a professional artist.

What we see now. The position of modern society is that people with persistent health impairments are just like everyone else, regardless of their pathologies. They should not be idealized, but at the same time, society should not turn away from their problems or limit their opportunities—this reflects the health of society. We see that people with disabilities can do sports, including professional sports, and do almost any professional activity or creative endeavor.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was a standard submission to the journal. The article has undergone external peer review.

Peer Review File: Available at https://cdt.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/cdt-24-262/prf

Conflicts of Interest: Both authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://cdt.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/cdt-24-262/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Nabiyeva A, Lutsenko A, Shelepova T, et al. Rhinophyma in a Patient with Multibacterial Indeterminate Leprosy. IP Pavlov Russian Medical Biological Herald 2023;31:671-7. [Crossref]

- Zhang R, Shen C, Rao L. Cardiac echinococcosis secondary to hepatic echinococcosis: a rare case report. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther 2022;12:147-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gombrich EH. The story of art. London: Phaidon Press; 2016.

- Moola FJ, Posa S, Buliung R. Malevolent or Benevolent Brushstrokes?: Exploring the Depiction of Disability in Renaissance Paintings Using a Critical Disability Studies Lens. Canadian Journal of Disability Studies 2023;12:110-51.

- Abul K, Misir A, Buyuk AF. Art in Science: Jusepe de Ribera’s Puzzle in The Clubfoot. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2018;476:942-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Biernoff S, Johnstone F. What can art history offer medical humanities? Med Humanit 2024;medhum-2023-012763.

- Rachman S. Memento morbi: Lam Qua’s paintings, Peter Parker’s patients. Lit Med 2004;23:134-59; discussion 201-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fan BE. Reflections on a 19th century Qing dynasty portrait with neurofibromatosis type 1. Postgrad Med J 2024;qgae070. [Crossref] [PubMed]