Mediterranean lifestyle and cardiovascular disease prevention

Introduction

Recent guidelines for cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention tend to focus heavily on lifestyle modifications (i.e., healthy diet, smoking cessation, physical activity, healthy weight) due to their relatively low-cost and long-term potential effects (1,2). Adherence to Mediterranean diet is an established as protective factor against CVD risk (3-6); however, the spectrum of the mechanisms through which this protection is offered has not been completely clarified (7). It has been suggested that adherence to Mediterranean diet has a regulating effect on CVD risk factors (i.e., arterial blood pressure, cholesterol levels, insulin resistance, endothelial function and inflammation), although all these effects are linked to an apparent synergy of the entire dietary pattern, rather than being the result of any of its components separately (8,9), implying that the Mediterranean dietary pattern should be considered as an entity with respect to disease prevention (10,11). Moreover, recently UNESCO described Mediterranean diet as intangible heritage and the definition was not restricted to the nutritional aspects of food and food group consumption, but was extended to include lifestyle parameters such as “eating together”, “sharing food”, “socializing”, “affirming and renewing family, groups and community identity” and being involved to food production and cooking (12).

Under the same rationale, the pictorial model: the Mediterranean diet pyramid has been updated to include incorporated social and other lifestyle aspects (i.e., adequate rest, conviviality, culinary activities, food sharing etc.) in addition to the dietary habits, suggesting that the overall lifestyle could have protective effects that are not only linked to specific nutrients and food groups, but also to psychological, social and physical behaviors that are present in Mediterranean lifestyle (13). For instance, habits such as daytime nap (siesta), going out with friends, living in a rural region, shared family meals and living with others constitute the Mediterranean lifestyle and are believed to have beneficial health effects; nevertheless, the exact mechanisms have not been investigated in-depth (14-16).

Furthermore, despite all the research studies that evaluated the effect of Mediterranean Diet on CVD risk, no attempt has been made to explore the Mediterranean lifestyle as a composite of dietary, social and demographic parameters that are usually present in Mediterranean populations. Thus, the aim of the present study was to investigate the broad spectrum of the links between Mediterranean lifestyle and CVD risk factors, among elderly who reside in the Mediterranean basin.

Methods

Methodology

The Mediterranean islands (MEDIS) study is an ongoing, large-scale, multinational project in the Mediterranean region, supported by the Harokopio University and the Hellenic Heart Foundation, which aims to explore the association between lifestyle habits, psycho-social characteristics and living environment, on cardio-metabolic factors, among older people (>65 years), residing in the Mediterranean basin.

The MEDIS Study’s sample

During 2005–2015, a population-based, multi-stage convenience sampling method was used to voluntarily enroll elders from the 21 MEDIS: Republic of Malta (n=250), Sardinia (n=60) and Sicily (n=50) in Italy, Mallorca and Menorca (n=111), Republic of Cyprus (n=300) and the Greek islands of Mitilini (n=142), Samothraki (n=100), Cephalonia (n=115), Crete (n=131), Corfu (n=149), Limnos (n=150), Ikaria (n=76), Syros (n=151), Naxos (n=145), Zakynthos (n=103), Salamina (n=147), Kassos (n=52), Rhodes and Karpathos (n=149), Tinos (n=129), as well as the rural region of east Mani (n=295, 157 men aged 75±7 years and 138 women aged 74±7 years) (a Greek peninsula, which is the southeast, continental area of Europe, with a total population of 13,005 people (census 2011), has morphological and cultural specificities, which are not come across in the rest of Greece. It is an infertile and rocky peninsula, of which the linkage to ancient Sparta bequeaths to its residents-mainly self-employed fishermen and farmers, living in small villages, and keeping on a lot of their activities) the traditional way of living of the past. Their nutrition is austere and frugal, based on the products of their land with the olive oil gaining an eminent position) (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mani_Peninsula), were included. According to the design of the study, individuals who resided in assisted-living centers, had a clinical history of CVD or cancer, or had left the island for a considerable period of time during their life (i.e., >5 years) were not included in the study; these exclusion criteria were applied because the study aimed to assess lifestyle patterns that were not subject to modifications due to existing chronic health care conditions or by environmental factors, other than living milieu. A group of health scientists (physicians, dietitians, public health nutritionists and nurses) with experience in field investigation collected all the required information using a quantitative questionnaire and standard procedures. Thus, for the present work information from 1,369 men, aged 75±8 years and 1,380 women, aged 74±7 years was analyzed; stratified into two main groups, i.e., people from the continental region of Mani, and the rest of MEDIS’ study participants.

Bioethics

The study followed the ethical considerations provided by the World Medical Association (52nd WMA General Assembly, Edinburgh, Scotland; October 2000). The Institutional Ethics Board of Harokopio University approved the study design (16/19-12-2006). Participants were informed about the aims and procedures of the study and gave their consent prior to being interviewed.

Evaluation of clinical characteristics

All of the measurements taken in the different study centers were standardized and the questionnaires were translated into all of the cohorts’ languages following the World Health Organization (WHO) translation guidelines for tools assessment (www.who.int/substance_abuse/research_tools/translation/en/).

Weight and height were measured using standard procedures to attain body mass index (BMI) scores (kg/m2). Diabetes mellitus (type 2) was determined by fasting plasma glucose tests and was analyzed in accordance with the American Diabetes Association diagnostic criteria (glycated haemoglobin A1C >6.5% (48 mmol/mol) or fasting blood glucose levels greater than 126 mg/dL (7.0 mmol/L) or 2-h plasma glucose >200 mg/dL (>11.1 mmol/L) during an oral glucose tolerance test-OGTT- or a random plasma glucose >200 mg/dL (>11.1 mmol/L) or they have been already diagnosed with diabetes). Participants who had blood pressure levels >140/90 mmHg or used antihypertensive medications were classified as hypertensive. Fasting blood lipids levels (HDL-, LDL-cholesterol and triglycerides) were also recorded and hypercholesterolemia was defined as total serum cholesterol levels >200 mg/dL or the use of lipid-lowering agents according to the NCEP ATP III guidelines (17). The coefficient of variation for the blood measurements was less than 5%.

Evaluation of lifestyle and socio-demographic characteristics

Dietary habits were assessed through a semi-quantitative, validated and reproducible food-frequency questionnaire (18). Through this questionnaire, trained dietitians estimated the mean daily energy intake and the mean percentage of carbohydrates contribution in the total energy intake. To evaluate the level of adherence to the Mediterranean diet, the MedDietScore (possible range, 0−55) was used (19). Higher values for this diet score indicate greater adherence to the Mediterranean diet. Participants were encouraged to report on the history of their diet (i.e., number of years this dietary pattern had been in place). Basic socio-demographic characteristics such as age, sex, number of friends and family members, frequency of going out with friends and/or family per week, numbers of holiday excursions per year, living alone or with family, education level (described with school years), residing in rural or urban area, as well as lifestyle characteristics, such as smoking habits and physical activity status, data on frequency of sleeping during the day (siesta) where having a siesta (daytime nap) for more than five days per week (20), were also recorded. More particularly, current smokers were defined as smokers at the time of the interview. Former smokers were defined as those who previously smoked, but had not done so for a year or more. Current and former smokers were defined as ever smokers. The remaining participants were defined as occasional or non-smokers. Physical activity was evaluated in MET-minutes per week, using the shortened, translated and validated into Greek, version of the self-reported International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) (21). Frequency (times per week), duration (minutes per session) and intensity of physical activity during sports, occupation and/or leisure activities were assessed. Participants were instructed to report only episodes of activity lasting at least 10 minutes, since this is the minimum required to achieve health benefits. Physically active were defined those who reported at least 3 MET-minutes. Symptoms of depression during the past month were assessed using the validated Greek translation of the shortened, self-report geriatric depression scale (GDS) (22-24). The GDS questionnaire included ‘yes or no’ items where responses were coded one (for answers that indicate depressive symptoms) and zero (for answers that do not indicate depressive symptoms), yielding a possible total score between 0 and 15. Higher values indicate more severe depressive symptomatology.

Further details about the MEDIS study protocol have been extensively been published elsewhere (25,26).

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation for variables following normal distribution or median (inter-quartile range) for variables not following normal distribution. Normality was tested using P-P plots. Differences in continuous variables between males and females were evaluated with the Student’s t-test for normally distributed parameters and the Mann-Whitney test for non-parametric variables. Nominal variables are presented as frequencies and relative frequencies (%). Pearson’s chi-square test was used to assess the association between two nominal variables.

Binary logistic regression models were used to evaluate the association between participants’ characteristics (i.e., age, sex, BMI, physical inactivity, smoking habits, siesta habit, educational status, living alone, level of adherence to Mediterranean diet, GDS, number of friends and family members, frequency of going out with friends and family, number of holiday excursions per year) and presence of type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension and hypercholesterolemia. Results are expressed as odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). All statistical tests were performed for 2-tailed hypotheses. Type I error was predefined at 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed in IBM SPSS version 23.0 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.).

Results

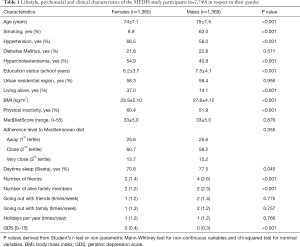

The overall prevalence of the traditional CVD risk factors in the study sample were 62.3% for hypertension, 22.3% for diabetes mellitus and 47.7% for hypercholesterolemia. One out of five participants was found to have no abnormal CVD risk factors, 37.1% had only one, 32.2% had two co-existing CVD risk factors and 10% had all the above CVD risk factors. Moreover, 35.2% of the study sample was habitual smokers at least once in their lives, whilst approximately 15.6% were current smokers. The mean level of adherence to Mediterranean diet—as assessed through the MedDietScore- was 33±5 out of 55 maximum score, more than half of the individuals were sedentary (56.2%), whilst the mean BMI was 28.3±4.7 kg/m2. Descriptive, lifestyle and clinical characteristics of the study sample, divided by gender, are summarized in Table 1.

Full table

Males, when compared to females, were more likely have been smokers (62% vs. 8.9% respectively, P<0.001), slightly older (75 vs. 74 years of age, respectively, P<0.001) with higher educational level (7.5 vs. 6.2 school years respectively, P<0.001). Moreover, males were less likely to be hypertensive as compared to females (58% vs. 66.5% respectively, P<0.001), a trend that was observed for hypercholesterolemia as well (40.8 vs. 54.9 respectively, P<0.001). Men had also significantly lower BMI than women (27.8 vs. 28.9 kg/m2 respectively, P<0.001), were less likely to be sedentary (51.9% vs. 60.4% respectively, P<0.001) and less likely to live alone (14.1% vs. 37.0% respectively, P<0.001). Moreover, males tended to sleep during the day more often than females (77.5% vs. 70.8% respectively, P=0.045), had more friends (4 vs. 2 respectively, P<0.001), were more likely to have more than two family members alive (P<0.001) and less likely to have depressive symptoms (P<0.001). No differences between genders were revealed for other social parameters such as the frequency of going out with family or friends, the number of holiday excursion per year and the characteristics of the residential area (approximately 58% of both genders resided in urban regions). Furthermore, no significant differences were detected for the level of adherence to Mediterranean diet or the prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (all P values >0.05).

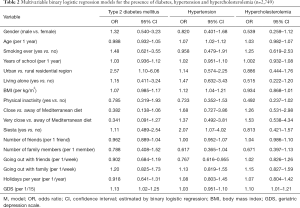

When multivariable binary logistic model was implemented with the presence of type 2 diabetes mellitus as the dependent variable, residing in an urban rather than a rural region was an independent positive predictor for the presence of type 2 diabetes mellitus OR =2.57, 95% CI: 1.10–6.06) after adjusting for gender, age, smoking status, education level, physical inactivity, level of adherence to Mediterranean diet, BMI, depressive symptomatology and social parameters (i.e., living alone, midday sleep (siesta), number of friends and family members, frequency of going out with family or friends, number of holiday excursions per year) (Table 2, Model 1). Furthermore, the estimated score in GDS was also an independent positive predictor for the presence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (OR =1.13, 95% CI: 1.02–1.25) after adjusting for gender, age, smoking status, education level, physical inactivity, level of adherence to Mediterranean diet, BMI, residential region and social parameters (i.e., living alone, midday nap (siesta), number of friends and family members, frequency of going out with family or friends, number of holiday excursions per year) (Table 2, Model 1).

Full table

Furthermore, when multivariable binary logistic model was performed for the presence of hypertension, increasing age was an independent positive predictor (OR =1.07, 95% CI: 1.02–1.12) after adjusting for gender, smoking status, residential area, education level, physical inactivity, level of adherence to Mediterranean diet, BMI, depressive symptomatology and social parameters (i.e., living alone, midday sleep (siesta), number of friends and family members, frequency of going out with family or friends, number of holiday excursions per year) (Table 2, Model 2). In the same multi-adjusted model, other significant positive predictors of the presence of hypertension were increasing BMI (OR =1.12, 95% CI: 1.04–1.21), the habit of midday nap (OR =2.07, 95% CI: 1.07–4.02), whilst the frequency of going out with friends was significantly associated with less odds of hypertension presence (OR =0.767, 95% CI: 0.616–0.955) (Table 2, Model 2).

On implementing a multivariable binary logistic model with the presence of hypercholesterolemia as the dependent variable, the estimated score in GDS was the only independent positive predictor for the presence of hypercholesterolemia (OR =1.10, 95% CI: 1.01–1.21) after adjusting for gender, age, smoking status, education level, physical inactivity, level of adherence to Mediterranean diet, BMI, residential region and social parameters (i.e., living alone, midday sleep (siesta), number of friends and family members, frequency of going out with family or friends, number of holiday excursions per year) (Table 2, Model 3).

Discussion

In the present study the data is supports the theory that the health effects of the Mediterranean lifestyle extend beyond those provided by the Mediterranean diet. These include the benefits of frequent socializing with friends, which was inversely associated with the presence of hypertension, whilst frequent daytime sleeping called siesta was positively associated with hypertension presence in elderly, after adjusting for several confounders. Furthermore, the present study suggested that urban residential environment is associated with higher odds of type 2 diabetes mellitus in elderly population, with, depressive symptomatology in the elderly being a robust independent predictor for type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypercholesterolemia, but not for hypertension. This was the first study to investigate a broad range of lifestyle parameters and their role in CVD prevention and suggested that Mediterranean lifestyle -as a holistic entity- should be further examined as an independent predictor of CVD-risk among elderly, especially when in combination with Mediterranean diet.

As regards to the role of social life on CVD risk factors, the present study revealed that frequent socializing with friends was inversely associated with the presence of hypertension in elderly, although, no association between social life and other CVD risk factors was revealed. This is in accordance with prospective studies among elderly in Latin America, India and China where restricted networks were linked to significantly reduced survival time (27). These findings could be mainly attributed to the outcome of spending time with beloved people, which is thought to reduce psychological stress (28). The latter leads to the regulation of gonadal hormones and thus, reduced arterial stiffness and lower blood pressure (29). These findings are in accordance with a large prospective study, where 1-unit increase in the total average of negative social interaction score was associated with a 38% increased odds of developing hypertension within 4 years. This association was attributable primarily to interactions with friends, but also to negative interactions with family and partners (30).

Another important finding of the present work was that urban residents were almost twice as likely to have type 2 diabetes, independently of their physical activity status, as compared to rural residents. A potential explanation is that elderly individuals tend to use the public open spaces more than any other adult group. Thus, leisure time physical activity can be quite restricted for those living in urban regions, whilst elderly residents in rural areas may tend to have easier access to public open spaces. This leisure time activity could efficiently increase insulin sensitivity and glucose uptake and thus, reduce the risk of developing type 2 diabetes (31). Unexpectedly, adherence to Mediterranean diet was not associated with the presence of type 2 diabetes in the present study, but this could be explained by the consistent high average level of adherence to Mediterranean diet in the study sample.

Depressive symptomatology was positively associated with presence of type 2 diabetes in the present work, which is in accordance with a recently published prospective study suggesting that depression is strongly related to increased type 2 diabetes risk in later life (32). The most dominant explanation for this association is that depression is associated with disruption of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA)-axis, which increases blood concentrations of cortisol, leading to insulin resistance. Insulin resistance promotes the development of hypertriglyceridemia and subsequent hypercholesterolemia, suggesting that depression is one of the most aggravating factors for CVD onset in elderly (33). Conflicting evidence has been published regarding siesta and its role in CVD risk, with advocates suggesting that daytime sleeping promotes well-being, but opponents claiming that siesta is a masking indicator of metabolic abnormalities and should be further investigated (34).

Limitations

This is a cross-sectional survey and therefore lacks the ability to identify causal relationships. Although the MEDIS study utilized a comprehensive approach for the CVD risk factors, it was not a study that has been exclusively designed to address the psychosocial CV determinants. The measurements have been performed only on a single occasion and may be prone to measurement errors, but this methodology is commonly used worldwide, making the results comparable to other studies. Several lifestyle parameters such as socializing (frequency and with whom), siesta (daytime sleeping) habit and number of excursions per year are prone to seasonal variability, however, the participants were asked to recall the most representative information via guided conversation with trained personnel.

Conclusions

Frequent socializing and a rural residential environment were linked to lower odds of an increased CVD risk factors’ presence among elderly living in the Mediterranean basin, whilst midday sleeping (siesta) and depression were associated with higher odds. Holistic lifestyle assessment among elderly individuals should become an essential part of a new approach in geriatric clinical practice, to reduce the burden of CVD in this high-risk population. Moreover, in line with current active and healthy ageing international and national strategies (35), community-based campaigns and multi-stakeholder public policies should continue to be implemented and strengthened to encourage and facilitate positive lifestyle choices and behaviors, as well as increase social engagement, among the elderly.

Acknowledgements

We are, particularly, grateful to the men and women from the islands of Malta, Sardinia, Sicily, Mallorca, Menorca, Cyprus, Lesvos, Samothraki, Crete, Corfu, Lemnos, Zakynthos, Cephalonia, Naxos, Syros, Ikaria, Salamina, Kassos, Rhodes, Karpathos, Tinos and the rural area of Mani, who participated in this research. The MEDIS study group is: M. Tornaritis, A. Polystipioti, M. Economou, (field investigators from Cyprus), A. Zeimbekis, K. Gelastopoulou, I. Vlachou (field investigator from Lesvos), I. Tsiligianni, M. Antonopoulou, N. Tsakountakis, K. Makri (field investigators from Crete), E. Niforatou, V. Alpentzou, M. Voutsadaki, M. Galiatsatos (field investigators from Cephalonia), K. Voutsa, E. Lioliou, M. Miheli (field investigator from Corfu), S. Tyrovolas, G. Pounis, A. Katsarou, E. Papavenetiou, E. Apostolidou, G. Papavassiliou, P. Stravopodis (field investigators from Zakynthos), E. Tourloukis, V. Bountziouka, A. Aggelopoulou, K. Kaldaridou, E. Qira, (field investigators from Syros and Naxos), D. Tyrovolas (field investigator from Kassos), I. Protopappa (field investigator from Ikaria), C. Prekas, O. Blaserou, K.D. Balafouti (field investigators from Salamina), S. Ioakeimidi (field investigators from Rhodes and Karpathos), A. Foscolou (field investigator from Tinos), A. Mariolis, E. Petropoulou, A. Kalogerakou, K. Kalogerakou (field investigators from Mani), S. Piscopo (field investigators from Malta), J.A. Tur (field investigators from Mallorca and Menorca), G. Valacchi, B. Nanou (field investigators from Sardinia and Sicily) for their substantial assistance in the enrolment of the participants.

Funding: The study has been funded by the Hellenic Heart Foundation and the Graduate program of the Department of Nutrition and Dietetics, Harokopio University in Athens, Greece. Stefano Tyrovola’s work was supported by the Foundation for Education and European Culture (IPEP), the Sara Borrell postdoctoral programme (reference no. CD15/00019 from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII - Spain) and the Fondos Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER). Josep A. Tur was funded by grants PI11/01791, CIBERobn CB12/03/30038, and CAIB/EU 35/2001.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The study was approved by Institutional Ethics Board of Harokopio University (16/19-12-2006) and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

References

- Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, et al. 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Kardiol Pol 2016;74:821-936. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wong ND, Sperling LS, Baum SJ. The American Society for Preventive Cardiology: Our 30-year legacy. Clinical Cardiology 2016;39:627-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eguaras S, Toledo E, Hernandez-Hernandez A, et al. Better Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet Could Mitigate the Adverse Consequences of Obesity on Cardiovascular Disease: The SUN Prospective Cohort. Nutrients 2015;7:9154-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Ruiz-Canela M, Hruby A, et al. Intervention Trials with the Mediterranean Diet in Cardiovascular Prevention: Understanding Potential Mechanisms through Metabolomic Profiling. J Nutr 2016. [Epub ahead of print]. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tong TY, Wareham NJ, Khaw KT, et al. Prospective association of the Mediterranean diet with cardiovascular disease incidence and mortality and its population impact in a non-Mediterranean population: the EPIC-Norfolk study. BMC medicine 2016;14:135. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Panagiotakos DB, Georgousopoulou EN, Pitsavos C, et al. Ten-year (2002-2012) cardiovascular disease incidence and all-cause mortality, in urban Greek population: the ATTICA Study. Int J Cardiol 2015;180:178-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Panagiotakos DB, Georgousopoulou EN, Pitsavos C, et al. Exploring the path of Mediterranean diet on 10-year incidence of cardiovascular disease: the ATTICA study (2002-2012). Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2015;25:327-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Simopoulos AP. The Mediterranean diets: What is so special about the diet of Greece? The scientific evidence. J Nutr 2001;131:3065S-73S. [PubMed]

- Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Martin-Calvo N. Mediterranean diet and life expectancy; beyond olive oil, fruits, and vegetables. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2016;19:401-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jones-McLean EM, Shatenstein B, Whiting SJ. Dietary patterns research and its applications to nutrition policy for the prevention of chronic disease among diverse North American populations. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2010;35:195-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schulze MB, Hoffmann K. Methodological approaches to study dietary patterns in relation to risk of coronary heart disease and stroke. Br J Nutr 2006;95:860-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- UNESCO. Intangible Heritage Lists. 2012 [cited 2012 14/02/2012]. Available online: www.unesco.org

- Bach-Faig A, Berry EM, Lairon D, et al. Mediterranean diet pyramid today. Science and cultural updates. Public Health Nutr 2011;14:2274-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kamon Y, Okamura T, Tanaka T, et al. Marital status and cardiovascular risk factors among middle-aged Japanese male workers: the High-risk and Population Strategy for Occupational Health Promotion (HIPOP-OHP) study. J Occup Health 2008;50:348-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Perez-Ferre N, Del Valle L, Torrejon MJ, et al. Diabetes mellitus and abnormal glucose tolerance development after gestational diabetes: A three-year, prospective, randomized, clinical-based, Mediterranean lifestyle interventional study with parallel groups. Clin Nutr 2015;34:579-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Faquinello P, Marcon SS. Friends and neighbors: an active social network for adult and elderly hypertensive individuals. Rev Esc Enferm USP 2011;45:1345-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA 2001;285:2486-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tyrovolas S, Pounis G, Bountziouka V, et al. Repeatability and validation of a short, semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire designed for older adults living in Mediterranean areas: the MEDIS-FFQ. J Nutr Elder 2010;29:311-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Panagiotakos DB, Pitsavos C, Stefanadis C. Dietary patterns: a Mediterranean diet score and its relation to clinical and biological markers of cardiovascular disease risk. Nutrition, metabolism, and cardiovascular diseases NUTR METAB CARDIOVASC DIS 2006;16:559-68. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bursztyn M, Ginsberg G, Stessman J. The siesta and mortality in the elderly: effect of rest without sleep and daytime sleep duration. Sleep 2002;25:187-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Papathanasiou G, Georgoudis G, Papandreou M, et al. Reliability measures of the short International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) in Greek young adults. Hellenic J Cardiol 2009;50:283-94. [PubMed]

- Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res 1982-1983;17:37-49. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fountoulakis KN, Tsolaki M, Iacovides A, et al. The validation of the short form of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) in Greece. Aging (Milano) 1999;11:367-72. [PubMed]

- Panagiotakos DB, Kinlaw M, Papaerakleous N, et al. Depressive symptomatology and the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors among older men and women from Cyprus; the MEDIS (Mediterranean Islands Elderly) epidemiological study. J Clin Nurs 2008;17:688-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tyrovolas S, Haro JM, Mariolis A, et al. Successful aging, dietary habits and health status of elderly individuals: a k-dimensional approach within the multi-national MEDIS study. Exp Gerontol 2014;60:57-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tyrovolas S, Zeimbekis A, Bountziouka V, et al. Factors Associated with the Prevalence of Diabetes Mellitus Among Elderly Men and Women Living in Mediterranean Islands: The MEDIS Study. Rev Diabet Stud 2009;6:54-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Santini ZI, Koyanagi A, Tyrovolas S, et al. Social network typologies and mortality risk among older people in China, India, and Latin America: A 10/66 Dementia Research Group population-based cohort study. Soc Sci Med 2015;147:134-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Martinez M, Lopez-Garcia E, Guallar-Castillon P, et al. Social support and ambulatory blood pressure in older people. J Hypertens 2016;34:2045-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hu B, Liu X, Yin S, et al. Effects of psychological stress on hypertension in middle-aged Chinese: a cross-sectional study. PloS One 2015;10:e0129163. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sneed RS, Cohen S. Negative social interactions and incident hypertension among older adults. Health Psychol 2014;33:554-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bilal U, Diez J, Alfayate S, et al. Population cardiovascular health and urban environments: the Heart Healthy Hoods exploratory study in Madrid, Spain. BMC Med Res Methodol 2016;16:104. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Graham E, Au B, Schmitz N. Depressive symptoms, prediabetes, and incident diabetes in older English adults. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2016. [Epub ahead of print]. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto S, Matsushita Y, Nakagawa T, et al. Visceral Fat Accumulation, Insulin Resistance, and Elevated Depressive Symptoms in Middle-Aged Japanese Men. PloS One 2016;11:e0149436. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Moya L, Garcia-Noain A, Lobo-Escolar A, et al. Influence of siesta in the estimation of blood pressure control in patients with hypertension. Hypertension 2007;50:e14; author reply e15.

- Organisation WH. World Report on Ageing and Health 2015 [cited 2016 05/12/2016]. Available online: http://www.healthyageing.eu/sites/www.healthyageing.eu/files/resources/WHO%20report_HA2015.pdf