Paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in young and middle-aged athletes (PAFIYAMA) syndrome in the real world: a paradigmatic case report

Introduction

An enhanced risk of atrial fibrillation (AF) has been clearly documented in endurance athletes (top-class, elite and recreational) over the past decades (1-4). This risk typically ranges between 1.2- to 15-fold compared to the general and sedentary population, so that it can be paradoxically assumed that better is the cardiovascular fitness, higher is the incidence of AF (5-9). In this regard, we have recently described the ‘paroxysmal AF in young and middle-aged athletes’ (‘PAFIYAMA’) syndrome (10). Provided that other risk factors for AF and underlying conditions have been ruled out, the diagnostic algorithm and criteria of this syndrome include a number of conditions, classified as major and minor (10). Importantly, this new syndrome might be currently under-recognized and under-diagnosed, since its popularity remains limited so far. We describe here a paradigmatic case of PAFIYAMA syndrome, which may be possibly misdiagnosed and untreated when encountered in a different clinical setting.

Case presentation

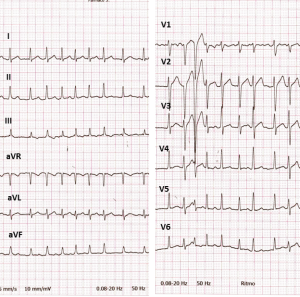

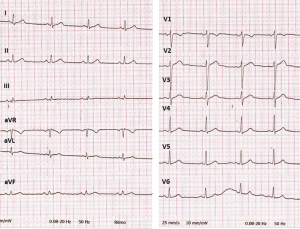

A 32 years old man (weight 76 kg, height 178 cm; BMI <25) was admitted to the Emergency Department (ED) complaining for palpitations, lasting for 3 hours. He had never smoked and other risk factors such as diabetes, hyperthyroidism, and hypertension could be ruled out. The electrocardiogram (ECG) was consistent with AF at high ventricular response (130–150 bpm) (Figure 1). All laboratory parameters were within the respective reference ranges, and laboratory screening for cocaine, amphetamine, and MDMA was negative for these drugs. The patient was administered with enoxaparin 8,000 IU and metoprolol 5 mg i.e., repeated for three times. After 12 hours of persistent AF, the patient underwent electrical cardioversion (biphasic DC shock, 150 J), which was immediately successful to restore the sinus rhythm. The ECG recorded after cardioversion was fully normal (Figure 2).

Interestingly, the patient reported an episode of paroxysmal AF (PAF), occurred during practicing strenuously training for an important martial arts competition (Wushu Kung Fu) 2 years before the current episode. This former event recovered spontaneously after approximately 6 hours, thus confirming the diagnosis of PAF. In the last 2 years the patient performed well, and his training in martial arts continued at high level (i.e., four to five 2–3-hour sessions a week). In the last 2 weeks, in addition to usual training, the patient was engaged in relocating his residence, carrying heavy furniture. He underwent echocardiography within a week from the ED discharge, showing a left ventricle (LV) hypertrophy: inter-ventricular septal thickness in diastole (IVSd): 11 mm; LV end-systolic diameter (LVEDD): 57 mm; posterior wall thickness, systole (PWTs): 16 mm; LV mass: 312 g. These data are in accordance with the concept of athlete’s heart, characterized by a balanced myocardial hypertrophy and ventricular dilation, i.e., eccentric LV hypertrophy. Likewise, a moderate left atrial (LA) dilation (49 mm), with normal ejection fraction (64%) and diastolic function, could be observed. The fact that diastolic function was not impaired with a high LV mass further supports the idea of hypertrophy in athlete’s heart, as a physiological adaptation. We did not request a chest X-ray due to the young age and good physical performance of the patient.

The patient was then discharged, with suggestion to reduce his training regimen. A Holter-ECG performed one month after ED discharge showed no signs of arrhythmia (nocturnal bradycardia, with minimum heart rate of 38 bpm between 2 and 5 a.m.), and the patient remained asymptomatic during the following six months of follow-up.

Therefore, based on the diagnostic algorithm of PAFIYAMA syndrome, including major criteria (onset as PAF, ≤60 years and male sex, prolonged practice of high-intensity exercise, and preserved ejection fraction), as well as five of the seven minor criteria (i.e., increased vagal tone with sinus bradycardia, LA enlargement, LV hypertrophy, increased LV wall thickness and LV mass, and normal diastolic function), this patient can be considered a paradigmatic case of this recently described syndrome.

Discussion

The potential clinical implications and the impact on patients’ lifestyle of PAFIYAMA syndrome are meaningful. Unfortunately, no effective strategies are currently available for predicting cardiac maladaptations in athletes who frequently practice high-intensity long-term endurance exercise (11). New-onset AF in young population is uncommon. For that reason, physicians should be aware about PAFIYAMA syndrome. In general, regular exercise may be safe in patients with this syndrome, although it depends of individual circumstances. Nonetheless, since most of the minor criteria are physiological adaptations (i.e., increased vagal tone with sinus bradycardia and LV hypertrophy, among others) triggered by practicing high-intensity endurance exercise, it seems reasonable to recommend reduction of both exercise volume and intensity. In fact, the physiological adaptations induced by exercise tend to disappear with training cessation. Notably, this recommendation may be overlooked by professional athletes. In these cases, antiarrhythmic drug and/or ablation may be the most effective approach (12).

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Informed Consent: The informed consent has been obtained from the only one patient of the case report.

References

- Mont L, Sambola A, Brugada J, et al. Long-lasting sport practice and lone atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J 2002;23:477-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Karjalainen J, Kujala UM, Kaprio J, et al. Lone atrial fibrillation in vigorously exercising middle aged men: case-control study. BMJ 1998;316:1784-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Molina L, Mont L, Marrugat J, et al. Long-term endurance sport practice increases the incidence of lone atrial fibrillation in men: a follow-up study. Europace 2008;10:618-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Baldesberger S, Bauersfeld U, Candinas R, et al. Sinus node disease and arrhythmias in the long-term follow-up of former professional cyclists. Eur Heart J 2008;29:71-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grimsmo J, Grundvold I, Maehlum S, et al. High prevalence of atrial fibrillation in long-term endurance cross-country skiers: echocardiographic findings and possible predictors--a 28-30 years follow-up study. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2010;17:100-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Andersen K, Farahmand B, Ahlbom A, et al. Risk of arrhythmias in 52 755 long-distance cross-country skiers: a cohort study. Eur Heart J 2013;34:3624-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aizer A, Gaziano JM, Cook NR, et al. Relation of vigorous exercise to risk of atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol 2009;103:1572-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thelle DS, Selmer R, Gjesdal K, et al. Resting heart rate and physical activity as risk factors for lone atrial fibrillation: a prospective study of 309,540 men and women. Heart 2013;99:1755-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Drca N, Wolk A, Jensen-Urstad M, et al. Atrial fibrillation is associated with different levels of physical activity levels at different ages in men. Heart 2014;100:1037-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sanchis-Gomar F, Perez-Quilis C, Lippi G, et al. Atrial fibrillation in highly trained endurance athletes - description of a syndrome. Int J Cardiol 2017;226:11-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Perez-Quilis C, Lippi G, Mena S, et al. PAFIYAMA syndrome: prevention is better than cure. J Lab Precis Med 2016;1:8. [Crossref]

- Perez-Quilis C, Lippi G, Cervellin G, et al. Exercising recommendations for paroxysmal AF in young and middle-aged athletes (PAFIYAMA) syndrome. Ann Transl Med 2017;5:24. [Crossref] [PubMed]