A critical review of addressing cardiovascular and other non-communicable diseases through a primary health care approach in the South-East Asia Region

Introduction

The eleven countries of the WHO South-East Asia Region (SEAR) constitute one-quarter of the global population, where nearly half of the population lives below poverty line and has limited access to health care. Approximately 120 million people in the region lack access to essential health services and the number can be more if non-communicable diseases (NCDS) are included. NCDs are currently responsible for 8.9 million deaths or 64% of all deaths in SEAR, of which, tragically, 4.4 million deaths occur prematurely between the ages of 30 and 69. Among NCDs, CVDs are responsible for almost 3.8 million deaths, which is almost 28% all the deaths (~13.8 million) and 43% of all the NCD-related deaths (~8.9 million deaths) in the SEAR as per Global Health Estimates, 2015 (1,2). Chronic respiratory diseases and cancers, each account for 15% of all NCD deaths. Achievement of sustainable development goals (SDG) of reduction of NCD mortality by one-third by 2030, depends critically on the reduction of CVD mortality as a top priority.

Countries in the region are reliant on primary health care systems for delivery of health services. While the primary health care approach offers a wider opportunity for NCD prevention and control, yet its potential is not fully tapped in the SEAR countries. In most countries, primary health care systems provide reactive and episodic responses. Lack of capacity to manage lifelong long-term chronic care and their comorbidities has been one of the key reasons for low performance in NCD control and management. Appropriate policies and cost-effective interventions are required to strengthen NCD services at the primary health care level. Health workforce, essential medicines and technologies, and information system are critical components for primary health care systems to respond to NCDs. As such reorientation and strengthening of primary health care systems is essential to improve the access to millions of people who lack access to NCD care in the Region. This article intends to review and describe the progress made in the South-East Asia Region, identifies implementation challenges and proposes potential way forward for further strengthening NCD prevention and control at the primary health care level.

Risk factors and determinants of NCDs in the South-East Asia

In the SEAR, the prevention and control of NCDs should be viewed within the broader phenomena of rapid urbanization and globalization. The urban population has increased from 29% in 2000 to 36% in 2015 (3) and the associated globalization is influencing lifestyles, dietary and other behavioural patterns of populations that have direct impact on NCDs. Approximately, 14.7% of the regional 18+ population is estimated to be physically inactive (4). Almost 32% of 15+ male population in SEAR smoke tobacco (5). Based on current trends, tobacco prevalence is projected to increase further in next 10 years in some of the large countries of the region such as Indonesia and Myanmar. Tobacco use is responsible for approximately 13% of deaths from NCDs, and harmful use of alcohol causes 4.6% of all deaths in SEAR. The population level salt consumption remains much higher than the recommended amount in most of the countries in the region (6).

Not surprisingly, there is growing number of population living with raised blood pressure and elevated blood sugar which increases the risks for stroke and coronary heart disease. In the SEAR, 25.1% and 8.6% of 18+ regional population have raised blood pressure and elevated blood glucose, respectively. As per the GHE, 2015 estimates, 5.7% of all CVD deaths are directly estimated to be caused by hypertensive heart disease in the SEAR. A substantial increase in age-standardized rates of deaths attributable to CVD from 376 per 100,000 (95% UI, 345–407) in 1990 to 398 per 100,000 in 2013 (95% UI, 352–443) in the South Asia was reported by Roth et al. (2).

Growing political support for NCD integration at the primary health care level

Since the endorsement of the 2011 UN High-level Political Declaration, countries in the SEAR have placed strong political emphasis to strengthen primary health care system to address NCDs. The regional NCD action plan and several other regional commitments and declarations have emphasized the need to strengthen and integrate NCD services at the primary health care level. The 2013 Delhi Declaration on combating high blood pressure (7), the 2015 Dili Declaration on tobacco (8), and the 2016 Colombo Declaration on strengthening NCDS at the primary health care level (9) provide the guiding framework for national level actions for risk factor prevention and NCD management at the frontline. An array of work streams is in progress in countries to contextualize and strengthen NCD care and coordination at the primary health in accordance with these commitments.

Contextualization of frontline health services for NCDs

Screening, early detection and management of NCDs is the core functions of primary health care services. There is notable progress made in countries (10). In Myanmar, early detection/screening for CVDs, diabetes and cancers (oral and breast cancer) was conducted in 20 townships by 2017 and is proposed to scale up in the remaining [240] townships in 2018 and 2019. In Indonesia, primary health care and community volunteers have been trained on risk factor screening and early detection programme at the community level using a community-based initiative (Posbindu), and has progressively expanded to 30,350 in 2017 (target is 80,000 villages must have one Posbindu). In India, accredited social health activists (ASHA), auxiliary nurse midwives (ANM) are conducting population-based NCD screening through profiling risk for NCDs in household family members above 30 years of age and strengthening referrals of suspected NCD cases to the designated health facilities. In Sri Lanka, Healthy Lifestyle Centres have been set up to improve screening and management of NCDs (11). In Timor-Leste, screening programme uses a household approach. One of the major drawbacks of early detection and screening programmes is that ongoing screening activities may not be adequately linked to continuity of care.

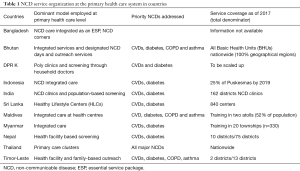

Countries are also adopting evidence-based protocols to standardize management of CVDs, hypertension, diabetes and chronic respiratory diseases at the primary health care level (10). Cascade trainings were being organized to train primary health workers to implement essential NCD services. Bhutan, Indonesia, Maldives, Myanmar, Sri Lanka and Timor-Leste have adapted the WHO package of essential NCD (WHO PEN) interventions to their national contexts while others such as India and Thailand have developed national NCD management protocols. The PEN interventions have been scaled up nationwide in Bhutan while others were rapidly scaling up the services (Nepal in 10 districts out of 75 districts have initiated PEN services, 840 centres Healthy Lifestyle Centres have been identified in Sri Lanka; two of the 13 districts in districts in Timor-Leste have started PEN services and in the Maldives 2 geographical regions (atolls) covering fifty percent of the country’s population been trained on PEN services). Indonesia has a plan to cover 25% of government-mandated community health clinics (Puskesmas) by 2019. The PEN pilots have been conducted in Bangladesh and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK). Also to global HEARTS tools have been adapted in Nepal while India, and Thailand are improving hypertension control programme through the Resolve to Save Lives Project. In Thailand, in order to address the increasing work load of primary health workers, more than 400 primary care (PC) clusters have been established in 2016 and plans are to increase to 6,500 clusters by 2026. A summary of service focus and recent initiatives to strengthen frontline NCD services among the SEAR countries are documented in Table 1.

Full table

Reorganizing PHC staffing and capacity building for NCD services

The availability of adequate numbers and right skills-mix of PHC workforce is the key to delivering a good quality NCD services. This should be supported by strong workforce policies and effective workforce deployment mechanisms. Notable steps are underway to strengthen the existing staffing by introducing new positions or creating new health professional cadre to strengthen NCD health service delivery (10). In Sri Lanka, the Ministry of Health has sanctioned two medical officer posts in the primary health care institutions. Further decisions have been taken to recruit community nurses in view of improving NCD care in communities. Similarly, in India additional staff nurses are appointed at PHC level in districts where population-based NCD screening is introduced. In Nepal, designated medical officers at the primary healthcare centres and health assistants at the health posts level have been appointed as the PEN focal points. PEN trained focal points have also been assigned at District Health Offices.

While a medical doctor remains the primary prescriber for NCD drugs in most countries, there are visible variants in Bhutan, Myanmar and Nepal where non-physicians (mid-level) primary health care workers are authorized to prescribe medicines for non-complicated hypertension, diabetes, and chronic respiratory diseases in primary health care level. Efforts will be worthwhile to institutionalize competency-based in-service training of primary health care workforce on early detection, patient management and organization of NCD services. Assigning tasks to mid-level health care workers should be advocated to accelerate screening and early detection programme for NCDs.

Essential medicines and diagnostics for NCD management at PHC level

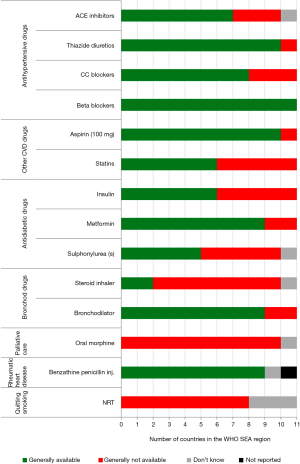

Primary health care systems should be well equipped with nationally agreed standards of essential drugs and medicines for managing the major NCDs. Essential medicines for management of hypertension, chronic respiratory medicines and access for prophylaxis treatment of rheumatic heart disease (RHD) are generally available while oral morphine and nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) are not available in all countries as shown in Table 2 (12). To reduce the variability in coverage and unequal access, India introduced the “Free Drugs and Diagnostics Service” initiative containing a minimal set of essential diagnostics for different levels of public facilities across the states which includes newer drugs and equipment for cancer, palliative care, cardiovascular diseases, COPD, CKD within the national list of essential medicines (NLEM) 2015. Laboratory capacities at NCD clinics of community health centres and district hospitals for conducting confirmatory diagnostic tests and population-based screening including random blood sugar testing for diabetes have been enhanced (12). Similar initiatives have been introduced in countries to improve access to essential medicines and diagnostics for NCDs.

Full table

In general, basic equipment such as blood-pressure measuring instrument, weight and height measurement scales are available in health facilities in all countries. Bhutan, India, Myanmar, Nepal and Sri Lanka Timor-Leste have introduced diagnostic services such as use of glucometer and lipid analysers in primary health care facilities (10,12). However, there are still gaps in essential laboratory services. Only Bangladesh, Indonesia and Sri Lanka reported providing blood cholesterol testing at the PC level and the majority of eleven countries do not have test strips for urine albumin in primary health care level (10).

In the areas of supplies and logistics, public health facilities often experience stock-outs of essential medicines and diagnostics. Gaps remain in the rational selection, and supply chain management for PC. Certain key essential medicines such as insulin are still unaffordable due to lack of generic competition and morphine is highly restricted. High cost new therapies for cancer, medical devices (stents) are grossly inaccessible to the poor. In the recent years, there has been a notable increase in domestic funding for primary health care activities for NCDs through national funding (10). However, total spending on primary health care for NCDs is far from adequate; more resources are needed to deliver comprehensive and quality NCD care at PC level in all countries (Figure 1). NCDs pose growing demand for lifelong treatment which needs policies that protect from catastrophic health spending for care.

Building community linkages for NCD care

Frontline NCD health services should be actively linked to the communities and catchment populations they serve including those who are unable to access care due to economic and social barriers. Tobacco brief interventions have been implemented through pilot projects in Bangladesh, Bhutan and DPR Korea, Indonesia and Timor-Leste. Indonesia has trained Quitline staff and provides tobacco Quitline services (free toll number 08001776565). India stepped up health promotion activities with the involvement of community, civil society, community-based organizations, schools in addition to outreach camps and clinics in 390 districts of the country. Village Health Sanitation and Nutrition Committee was identified as a platform for community awareness on NCD risk factors under the “population-based NCD screening” initiative of NPCDCS. A national health campaign {branded “My Year 2074 [2017]: If I am healthy, my nation is healthy”} with five key concrete commitments for all modifiable NCD risk factors has been launched in Nepal. Community-based alcohol outreach activities have been implemented in Bhutan, Sri Lanka and Timor-Leste. Bhutan and Timor-Leste reported community-based physical activity promotions and the two countries also reported community activities to improve household air quality. In all countries, expansion of community-based linkages should be further improved to increase the coverage of services.

Quality assurance systems of NCD services at primary health care level

Increasing coverage of services should be supported by ensuring good quality of NCD services which is yet to be established in most countries. Recent STEP surveys in SEAR member states, show substantial proportion of the people who were aware of their diagnosis of diabetes or raised blood pressure were not on treatment (treatment gap). In addition, a substantial proportion of people had uncontrolled BP or raised blood sugar levels despite being on treatment (13). Assessments done in countries [India hypertension study (14), Bhutan PEN clinical audit (15), assessment of healthy lifestyle in Sri Lanka (16), assessment of two districts in Nepal] support these findings. Among countries, Thailand has a notable initiative for quality assurance systems for NCD clinic quality introduced in 2014 through use of qualitative indicators to enhance performance of NCD services through “NCD Clinic Plus”. PEN clinical audit was conducted in Bhutan in 2016 to assess the quality of NCD service delivery. Supportive supervision tools and checklists are being improved as part of the PEN programme in Maldives, Nepal and Timor-Leste. In 2017, Nepal further enhanced monitoring systems for PEN services through Global HEARTS programme. Indonesia has included NCDs as a criterion for accreditation for primary health care services. India has revised monthly reporting forms to strengthened monitoring and supervision of field-level NCD screening activities. In most countries, there are weak patient level data, and information is still retained on paper (17). Patient tracking and follow up needs to be strengthened for drug adherence and patient outcome.

Way forward: opportunities for strengthening NCD management at primary health care level

PHC systems need better capacity to provide comprehensive first line care to handle multiple NCD morbidities. Most of the primary health care systems in the Region were traditionally designed for maternal and child health interventions, and communicable diseases. Both structural and systemic reforms are required to deliver screening programmes, early detection and provide comprehensive NCD care at the primary health care level. These will require broad systems-wide reforms that focus on improving PHC health workforce, provision of supplies and medicines and enhancing service delivery policies are the cornerstone to the success of PHC approach for delivery of NCD services.

Building competent primary health care workforce

Classic issues of health workforce shortage, poor competency, maldistribution and inadequate skills-mix prevail in the region. Countries need to invest in boosting the primary health workforce competencies and improve team-based care at health settings. Training of mid-level health workers, nonspecialized and non-physician health workers can be an effective solution to address insufficient of health workforce. Ministries of Health will need to promote and collaborate with health workforce training institutions to strengthen both pre- and in-service training. Additionally, new cadre such as nutritionists, laboratory technicians, pharmacists and health educators and counsellors should be trained and deployed in the primary health care system to deliver NCD services.

Considering the reality that every country operates within limited resources for health, governments should focus on balancing investment on overspecialization of health workers which takes focus out of primary health care workforce. While the extent of political ownership for PHC varies considerably across member states, constant advocacy is needed to invest and prioritize building the primary health care system. Furthermore, specialists and professionals should be given greater roles to lead and engage in development and reforms of primary health care system to build acceptances to primary health care approaches to NCD care. Coalitions of academics, civil society representatives and government experts should be mobilized for advocating NCD services in PC networks.

Improve service delivery and gate keeping

At present, there is minimal gate-keeping between primary and hospital levels leading to cost inefficiencies. Effective gate keeping is possible only when the users have confidence in services available at the primary health care level. Health facilities should be equipped with essential medicines, and diagnostics for common NCDs agreed by national standard and managed by trained health workers to retain the trust in the primary health care services. Both vertical and horizontal coordination should be improved to build credible PHC system that can efficiently provide screening, early detection and NCD management.

The availability of essential medicines and basic technologies and engagement of public and private sectors should be promoted. Procurement and distribution systems should be improved to ensure availability of essential diagnostic tools and medications at local primary healthcare clinics. While expanding the coverage of essential NCD services, it is necessary to guarantee an acceptable level of quality to enable effective gate keeping and increase efficiency of health services by increasing case detection and improving service utilization. Prescribing practices of care providers, and support for appropriate and timely referrals of severe and complex cases to higher centers should be ensured.

Contextualize the model of care

Translational research and knowledge on NCDs models of service delivery at primary health care level and information system for health systems response are important. While health information systems in all countries have incorporated selected NCD indicators, periodic independent assessments of health facilities performance, NCD-related essential drug surveys to assess rational use, availability and affordability of key NCD drugs and studies of service utilization to understand incentives and disincentives for PHCs should be improved. Continuous quality improvement and performance measurement of service delivery at primary health care should be institutionalized. Cross-country sharing of initiatives such as periodic standardised quantitative assessments and evaluations of NCD services should be widely promoted.

Investment in primary health care and NCD services

Political championing to mobilize the required funding for effective integration of NCDs in primary health care is a priority. Countries need to increase fiscal allocation for primary health care NCD services from national resources that is explicitly linked to social protection of the poor and reduction of out-of-pocket payment to enhance the universal health coverage. Governments should explore different arrays of financing mechanisms for primary health care services such as through dedicated taxation for health, together with development of clear ‘benefit package’ from the dedicated taxation.

Conclusions

Addressing NCD burden requires a PHC focus providing a people-centric, comprehensive, integrated and equitable care-built on the principles of the primary health care. NCD care needs to be effectively integrated within the existing primary health care system. The ongoing initiatives and evolution of primary health care systems among the countries in the region provide unprecedented opportunities to improve management of NCD services through primary health care facilities located nearest to the communities. However, sustained efforts are needed to rapidly scale up NCD services to readjust PHCs to attain transformative changes for integrating NCD control at primary health care systems to achieve national NCD targets. This will require additional investment in prioritizing competent health workforce, essential medicines and diagnostics and a good information system, which are essential components of credible primary health care system.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- World Health Organization. Global Health Estimates 2015: Burden of disease by Cause, Age, Sex, by Country and by Region, 2000-2015. Geneva, 2016.

- Roth GA, Johnson C, Abajobir A, et al. Global and Regional Patterns in Cardiovascualr Mortality: from 1990 to 2013. Circulation 2015;132:1667-78. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- World Bank. World Bank Indicators. Washington DC, 2015.

- World Health Organization. Prevalence of insufficient physical activity among adults: Data by WHO Region. Available online: http://apps.who.int/gho/data/view.main.2482?lang=en

- World Health Organization. WHO global report on trends in prevalence of tobacco smoking 2000-2025, second edition. Geneva, 2018.

- Moha S, Prabhakaran D. Review of Salt and Health: Situation in South-East Asia Region. 2013. Technical Paper.

- World Health Organization. Health Ministers adopt New Delhi Declaration to combat high blood pressure. 2013. Available online: http://www.searo.who.int/mediacentre/releases/2013/pr1562/en/

- World Health Organization. Dili Declaration on Tobacco Control: Sixty-eight Session of the Regional Committee. September, 2015.

- World Health Organization. Colombo Declaration: Strengthening Health Systems to Accelerate Delivery of Noncommunicable Diseases Services at the Primary Health Care Level. 2016.

- World Health Organization. Regional Office for South-East Asia Regional Office, "Strengthening Health Systems to Accelerate Delivery of Noncommunicable Diseases Services at the Primary Health Care Level: A one-year progress review of the implementation of the 2016 Colombo Declaration on NCDs. New Delhi, 2017.

- Mallawaarachchi DSV, Wickremasinghe SC, Somatunga LC, et al. Healthy Lifestyle Centres: a service for screening noncommunicable diseases through primary health-care institutions in Sri Lanka. WHO South East Asia J Public Health 2016;5:89-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. National capacity for prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases in WHO South-East Region. Results from NCD country capacity survey 2017. 2018.

- Travis P. Not business as usualL providing NCD services at the frontline. SEA Regional forum to accelerate NCD prevention and control in the context of the SDGs. 2017.

- Valan AS, Yadav R, Shaukat M, et al. Review of Hypertension and Diabetes Service Delivery System in Selected Districts under National Programme for Prevention and Control of Cancer, Diabetes, Cardiovascular diseases and Stroke (NPCDCS), India, 2015. New Delhi, 2016.

- World Health Organization. Clinical Audit of Package of Essential Non Communicable Diseases (PEN) Interventions in Primary Health Care, Bhutan 2016. 2017.

- University of Colombo. Department of Community Medicine, An assessment of the major noncommunicable disease programme in secondary and primary health-care institutions, Sri Lanka.

- World Health Organizatio. Summary: South-East Asia Regional Forum to Accelerate NCDs Prevention and Control in the Context of the SDGs. New Delhi, 2017.