Extra-cardiac comorbidities or complications in adults with congenital heart disease: a nationwide inpatient experience in the United States

With a great interest, we read the article by Neidenbach et al. on non-cardiac comorbidities in German adults with congenital heart disease (ACHD) (1). ACHD always bear an increased risk of developing concomitant non-cardiac comorbidities and complications and impose a great healthcare burden (1). However, this study being a single-center analysis might lack generalization for any other larger population. Limited large-scale data from the United States (US) on this focus incited us to write this correspondence. Gilboa et al. estimated nearly 2.4 million people living with CHD (1.4 million adults, 1 million children) in the US in 2010 (2). To have a better nationwide prospect of the current scenario, we looked at the extra-cardiac comorbidities among ACHD patients hospitalized in the US using the National Inpatient Sample database (NIS) for years 2013–2014.

The NIS is the publicly obtainable largest in-hospital dataset including all discharges regardless of payer status (https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp). It is developed under the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality-backed Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). It is illustrative of over 97% US population and comprehends data from >7 million annual in-hospital stays, if unweighted. The self-weighing design of NIS aids to yield the national estimates among 35 million hospitalizations annually. The IRB approval was not mandatory since the NIS is a deidentified dataset.

We identified ACHD-related hospitalizations using the Clinical Classification Software code 213 (exclusive of ICD-9 CM) diagnosis codes 747.5x 747.6x 747.8x. The CCS is a diagnostic classification system to collapse multiple ICD-9 CM codes into a category with smaller numbers to analyze the disease burden. Comorbidities were identified using pertinent ICD-9 CM codes (https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/comorbidity/Table2-FY12-V3_7.pdf). Descriptive statistics were performed to measure the incidence of comorbidities and continuous variables were expressed in percentage (%) and mean respectively. All statistical analyses were executed in SPSS Statistics 22 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

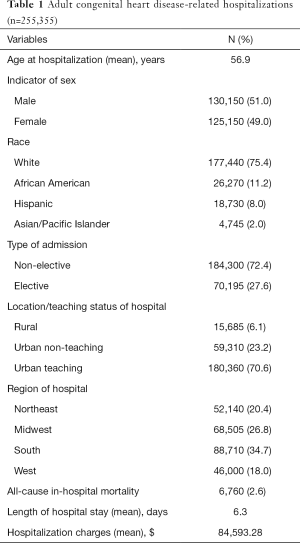

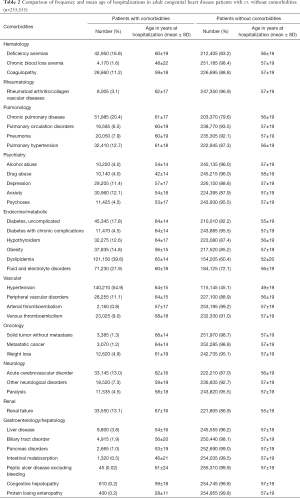

As shown in Table 1, we identified 255,355 ACHD-related hospitalizations from 2013 to 2014. The ACHD cohort (mean age 56.9 years, 51.0% males) predominantly comprised of white (75.4%) population having non-elective admissions (72.4%) to urban-teaching hospitals (70.6%), majorly in southern hospitals (34.7%) followed by Midwest region (26.8%). The leading subspecialties contributing to the most frequent comorbidities were vascular, endocrine, psychiatry, hematologic and pulmonary. As shown in Table 2, hypertension (HT) was the most common comorbidity (54.9%), followed by dyslipidemia (39.6%), fluid and electrolyte disturbance (27.9%), COPD (20.4%), uncomplicated diabetes mellitus (DM) (17.8%), deficiency anemias (16.8%) and obesity (14.8%). Acute cerebrovascular insult was present among 13.0% of the patients. Anxiety (12.1%) and depression (11.4%) were the most common psychiatric comorbidities. Gastric, hepatic and oncological comorbidities were least common. The lowest mean age (28±11 years) of hospitalization was among patients with protein-losing enteropathy. People suffering from cancer and renal failure were oldest, mean age of 68±14 and 67±16 years respectively. Mostly, ACHD subjects without extra-cardiac comorbidities were younger as compared to their counterparts except for individuals with psychiatric disorders. All-cause in-hospital mortality rate was 2.6% with a mean length of stay of 6.3 days and hospitalization charges of $84,593.28.

Full table

Full table

Metabolic and endocrinological comorbidities

Dyslipidemia (39.6%) was the most common metabolic disorder followed by uncomplicated DM (17.8%), obesity (14.8%) and hypothyroidism (12.6%). ACHD Patients hospitalized with endocrinological/metabolic disorders were older as compared to the one without these comorbidities, except in case of obesity. Neidenbach et al. reported a high prevalence of metabolic and endocrinological disorders in about 44% of the cases (1). However, the prevalence of diabetes was four times higher in our study (1). High prevalence of overt hypothyroidism can lead to hyperlipidemia, which could be accountable for the increased risk of coronary artery disease (CAD). Moreover, thyroid hormones also control the inotropic, chronotropic and lusitropic effects via regulating the intracellular signaling, cation transport and genetic reprogramming (3). Such hormonal abnormalities can increase the risk of CAD-related events and lethal arrhythmias (3).

Hematological and oncological comorbidities

Hematologic disorders comprising anemia and coagulopathy were recognized in about 16.8% and 11.2% of the study population, respectively. Hospitalization age was higher among the ACHD patients with hematological disorders as compared to those without these complications, however, subjects having chronic blood loss anemia were hospitalized at a very younger age. Iron, B12, and folate deficiencies are considered the major reason behind the deficiency anemias. Mukherjee et al. reported the prevalence of iron deficiency in about 47% of his study subjects (4). The primary reason behind the coagulopathy is possibly endothelial dysfunction, platelet activation, and hemostatic abnormalities. The occurrence of cancer, although rare, could also be a reason for coagulopathy. Cancer with and without metastasis was reported among 1.2% and 1.3% of cases respectively in contrast to 4.6% in the Neidenbach et al.’s. study (1). Patients suffering from cancer were oldest in the study cohort with a mean age 64 years.

Vascular comorbidities

Surprisingly, more than half (54.9%) of our study cohort was hypertensive which was three times higher than the findings by Neidenbach et al. (1). Common comorbidities like DM, CAD, and HT play a crucial role in the long-term outcome among ACHD patients. Total 11.1% of the patients in the present study had the peripheral vascular disease (PVD) comparable to the findings by Neidenbach et al. (1). A large number of patients, 9.0%, also suffered from venous thromboembolism. Venous congestion is common among the patients with Epstein’s anomaly or those undergone Fontan procedure (1).

Renal comorbidities

Renal failure was reported among 13.1% of the study population which is almost twice as higher compared to the Neidenbach et al. (1). Billett et al. reported 0.8% of the cases of the chronic renal disease among ACHD subjects (5). Renal dysfunction is not so uncommon extracardiac manifestations among the patients with CHD and had been reported in around 50% of the subjects in some studies (6). The major contributors of renal dysfunction in these cohorts is cyanosis, multiple cardiac surgeries, abnormal neurohormonal activation and traditional cardiovascular risk factors and long-term use of nephrotoxic medications. Compromised renal perfusion owing to the increased blood viscosity due to the reactive erythrocytosis also poses a greater risk of mortality among these patients.

Pulmonary disorder comorbidities

COPD was present in 20.0% and pulmonary hypertension (PAH) in 12.7% of the study subjects. The occurrence of PAH has been reported in up to 3–10% of the subjects (7). Surgical alteration of the lung, spinal and skeletal deformity or functional lung disorder, due to the hemodynamics of the ACHD are the primary reasons. Drugs like amiodarone lead to a negative impact on the pulmonary function and could lead to chronic pulmonary disease and PAH. It increases the mortality nearly twice as compared to the one without PAH (7). In CHD patients, PAH is lethal once it reaches the end-stage. However, if recognized in the early stage, PAH in ACHD patients is completely reversible (8). Anand et al. from the NIS database, looking for the trend of PAH-related hospitalization suggested a high prevalence of other comorbidities which can complicate the disease course (9). Presence of nearly similar burden of these comorbidities in our study suggests that PAH could be one of the factors influencing the occurrence of these complications.

Neuro-psychiatric comorbidities

Neidenbach et al. reported the burden of the neurological disorders in 18.02% of the cases as compared to a 13% in our study (1). The mean ages at hospitalization among ACHD patients with and without non-psychiatric comorbidities were comparable. However, ACHD patients having psychiatric comorbidities were younger at the time of hospitalization compared to those having no psychiatric illness. The incidence of a neurological sequel in ACHD has been reported to be 10 to 100 times higher than the general population with stroke prevalence ranging from 4% to 14% (1). Arrhythmia, hyperviscosity, vascular abnormality and paradoxical emboli due to the shunting could be the predominant reasons for this occurrence (3). High burden of cardiovascular risk factors like HTN, DM, and dyslipidemia are also contributory towards a high burden of acute cerebrovascular disease in these subjects. Anxiety (12.1%) and depression (11.4%) were the most common psychiatric comorbidities. Neidenbach et al. reported the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in around 6.3% of the cases (1). Kovacs et al. reported the high prevalence of mood disorder (33%) and anxiety disorder (26%) (10). We also noted an alarming 8% of alcohol/drug abuse prevalence in ACHD. These psychosocial complications could hamper the quality of life and outcomes.

Liver and biliary tract comorbidities

The prevalence of liver, biliary and pancreatic disorder was lower as compared to the one reported by Neidenbach et al. (1). Hepatic disease is common in CHD patients due to either the intervention or the result of congenital abnormality. Venous congestion driven by CHD or pulmonary disease (PAH) can lead to hepatopathy or hepatic ischemia (1). The use of drugs like amiodarone also adversely affects the liver. However, the occurrence of the gastrointestinal disorders or hepatic disease was lower as compared to the other organ system comorbidities. Biliary tract diseases, mostly biliary atresia, is common among infants and not so in adults.

Inaccessibility of information on the compliance to medications and a history regarding the level of care constraints can influence the actual prevalence of the comorbidities. The NIS, being an administrative database, coding error could lead to the over or under reposting of the study variables. Nevertheless, the large sample size allowed us to achieve the national estimates generalizable to a larger population.

The burden of extracardiac comorbidities among the NIS cohort in the US was diverse as compared to the German outpatient ACHD cohort. Our study reports a higher burden of endocrinological, hematological, metabolic, pulmonary, psychiatric, renal and rheumatological comorbidities as compared to the German cohort. However, the burden of gastrointestinal and hepatological comorbidities was higher in the German outpatient cohort. In addition, ACHD patients with non-cardiac comorbidities were older except for those suffering from the psychiatric illnesses as compared to ACHD hospitalizations without comorbidities.

Despite the existing cutting-edge surgical and medical interventions, patients with CHD always bear hazards of complications hampering the quality of life. It is imperative for the clinicians to understand the non-cardiac complications which a patient might encounter during a lifetime, and which could further complicate the management of ACHD and increases the risk of mortality.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Neidenbach RC, Lummert E, Vigl M, et al. Non-cardiac comorbidities in adults with inherited and congenital heart disease: report from a single center experience of more than 800 consecutive patients. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther 2018;8:423-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gilboa SM, Devine OJ, Kucik JE, et al. Congenital Heart Defects in the United States: Estimating the Magnitude of the Affected Population in 2010. Circulation 2016;134:101-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grais IM, Sowers JR. Thyroid and the heart. Am J Med 2014;127:691-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee S, Sharma M, Devgan A, et al. Iron deficiency anemia in children with cyanotic congenital heart disease and effect on cyanotic spells. Med J Armed Forces India 2018;74:235-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Billett J, Cowie MR, Gatzoulis MA, et al. Comorbidity, healthcare utilisation and process of care measures in patients with congenital heart disease in the UK: cross-sectional, population-based study with case-control analysis. Heart 2008;94:1194-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Buelow MW, Cohen SB, Earing MG. Renal dysfunction in adults with congenital heart disease. Prog Pediatr Cardiol 2016;41:47-9. [Crossref]

- Lowe BS, Therrien J, Ionescu-Ittu R, et al. Diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension in the congenital heart disease adult population impact on outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:538-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van der Feen DE, Bartelds B, de Boer RA, et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension in congenital heart disease: translational opportunities to study the reversibility of pulmonary vascular disease. Eur Heart J 2017;38:2034-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Anand V, Roy SS, Archer SL, et al. Trends and Outcomes of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension-Related Hospitalizations in the United States: Analysis of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample Database From 2001 Through 2012. JAMA Cardiol 2016;1:1021-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kovacs AH, Saidi AS, Kuhl EA, et al. Depression and anxiety in adult congenital heart disease: predictors and prevalence. Int J Cardiol 2009;137:158-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]