Provision of medical health care for adults with congenital heart disease associated with aortic involvement

Introduction

Congenital heart anomalies are the most common isolated congenital organ malformations with an estimated incidence of 8/1,000 live births for congenital heart disease (CHD) and every year more than 1.35 million children are born worldwide with CHD (1-3).

Today, almost all types of CHD have become amenable to surgical or interventional treatment and more than 90% of all affected patients reach adulthood (4-6). Accordingly, around 50 million adults with CHD (ACHD) live at present worldwide (1).

However, despite of all advances, ACHD are and remain chronically ill from their cardiac disease, and many affected patients still have residua and sequelae of their CHD which contribute to an increased morbidity and mortality compared to the normal population (7-13).

For most CHD, heart defect specific cardiac residua or sequelae have to be expected, including heart failure, cardiac arrhythmias, pulmonary vascular disease with pulmonary/pulmonary arterial hypertension and a risk of infective endocarditis (4,7,14).

In the meantime, there is increasing evidence that also aortic alterations become relevant in ACHD. However, the importance of aortic diseases in CHD has long been underestimated and remains an often-overlooked condition, although it gains importance with increasing age and complexity of CHD.

Because of the listed potential residua and sequels, almost all patients with native, interventional or surgically treated CHD require lifelong follow-up care. This is mostly offered by general practitioners, family physicians and general internists (i.e., “primary care”), sometimes by cardiologists and only in a minority of cases by specifically trained and experienced congenital cardiologists or by cardiac centers for ACHD.

The aim of the current survey was to acquire real world data on the health status of patients and/or the provision of health services in ACHD associated with aortic abnormalities by general practitioners, family doctors and general practitioners (i.e., “primary care providers”). We present the following article/case in accordance with the SURG guideline checklist (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/cdt-20-359).

Methods

Study cohort

In this cross-sectional clinical study, 563 patients from a tertiary care center for ACHD (Department of Congenital Heart Disease and Pediatric Cardiology, German Heart Center Munich, Technical University Munich, Munich, Germany) were included. Patients were consecutively included in the order that they presented at the institution and were not selected in prior. The study was part of a nationwide study to assess the care situation of the ACHD throughout Germany (“VEmaH study”). The survey has been approved by the institutional review boards of the Technical University Munich (157/16 S) and written informed consent was obtained from all participating patients before the start of documentation. Participation or non-participation in this study had no influence on the medical care of the patients. Guidelines on good pharmacoepidemiological practice (GPP) and data protection guidelines were followed.

Patient inclusion

Inclusion criteria for the present study were a confirmed diagnosis of CHD, and adult age (>18 years). Exclusion criteria were lack of cognitive competence to consent to research, and refusal to consent.

Medical records were reviewed for patient demographics, cardiac and non-cardiac diagnosis. Accordingly, patients were assigned to one out of six classes of diagnosis.

Questionnaire

As this is the first study to explore the “real world data” on the health status of patients and/or the provision of health services in ACHD, it was not possible to use a standardized and validated questionnaire. For this purpose, a questionnaire was specifically devised in cooperation with the Chair of Behavioral Epidemiology at the Technical University of Dresden and the German Heart Center Munich as tertiary care center for ACHD.

This questionnaire contains questions related to the sociodemographic situation, the CHD, co-morbidities, care providers for medical problems in general and CHD-related problems, individual demands of the patients for counselling, knowledge of specific care structures and problems with the care situation from the patient’s perspective. The questionnaire was completed either directly during the stay at the hospital or online on the homepage of the study (http://www.vemah.info).

Patient classification

At first stage, the patients were classified according to the underlying CHD and consecutively assigned to 1 of 6 major diagnosis groups depending on the type of the underlying CHD: complex CHD (I), disorders of the left heart/anomalies of the aortic valve or aorta (II), disorders of the right heart/ anomalies of pulmonary valve or pulmonary artery (III), primary left-to-right shunt lesions—either at pre-tricuspid or post-tricuspid level (IV), genetic syndromes (V), or other congenital non-classifiable congenital heart anomalies (VI).

According to the underlying pathological anatomy, pathophysiology, and epidemiological data from the recent literature, ACHD were divided into the two groups “at risk for developing aortopathy and/or manifest aortopathy” or “without risk of intrinsic aortopathy”.

The “aortopathy” in the current cohort was defined either depending on the underlying disease with “intrinsic” pathologic aortic alterations or depending on the reported absolute diameter of the aortic root or the ascending aorta. “Intrinsic” pathologic aortic alterations with abnormality of vessel architecture were presumed according to data from the literature for syndromic and non-syndromic congenital or hereditary congenital anomalies (15).

In the present survey, an absolute diameter of the aortic root or the ascending aorta of >38 mm in a normal sized adult was considered pathologic, without correcting the normal range for age, weight, sex or body surface area. This seems suitable for this overview survey, since the definition of a “normal aorta size” is still under discussion and robust data on aortic size in the “normal” population are missing (16), particularly in patients with CHD.

Statistical analysis

The data analysis was performed using SPSS 23.0 (IBM Inc., Armonk, NY, USA). All statistical evaluations of the data were pseudonymized and not person-related.

Descriptive statistical methods were used for data analysis and initial characterization of the study population. Differences between the groups were checked and evaluated using Chi-squared tests. T-tests were used for comparisons between mean values. Continuous data was expressed as mean ± standard deviation, categorical or interval scaled variables as absolute numbers or percentages. All occurring P values and tests for significance were performed two-sided. A P value <0.05 was considered significant.

Since multiple answers were permitted for some questions, the number of received answers may differ from the total number of study participants included.

Results

Study sample and patient characteristics

A total of 563 patients with a proven hereditary or congenital heart defect were suitable for the present analysis and were enrolled. The underlying anomaly could be assigned to one of six different main groups (I–VI) (Table 1). Out of the 563 consecutively enrolled patients with CHD 320 (56.8%) had a risk of developing aortopathy. Of the 320 patients at risk, 187 (33.2% of the total number) had a proven aortopathy according to medical notes or by definition (Table 1).

Full table

Epidemiological data

The mean age of all patients at the time of the survey was 35.8±12.1 years (range, 18 to 86 years). Most patients were in their third, fourth and fifth decade of life (n=455; 80.8%). Thirty-five patients (6.2%) were younger than 20 years, 73 older than 50 years (13.0%). In terms of gender distribution, 279 patients (n=49.6%) were female.

Comparing the age distribution within the two groups “at risk/manifest aortopathy” and “without intrinsic aortopathy”, the patients at risk were significantly younger [34.3±10.8 years (range, 18 to 86 years) versus 37.7±13.3 years (range, 18 to 77 years)] and female patients were fewer [40.3% (n=129 of 320) versus 61.7% (n=150 of 243)].

The body mass index of all included patients was 24.7±4.4 kg/m2 (range, 13.8–49.3 kg/m2), with no significant difference between both groups at risk/manifest aortopathy (24.6±4.1 kg/m2; range, 13.8–41.9 kg/m2) compared to the group w/o intrinsic risk (24.9±4.8 kg/m2; range, 16.4–49.3 kg/m2) (P=0.480).

Basic medical care for general, CHD-independent medical problems

As shown by the study data, basic medical care was in the entire group of ACHD in 88.9% (n=501 answers) provided by family doctors, general practitioners, internists and sometimes physicians of another specialty as first consultation partners.

When asked about their primary medical care provider for general, CHD-independent, medical issues, in the group “at risk/manifest aortopathy” 337 answers were given. Eighty-nine point four percent (n=286) of the responders consulted a general practitioner/family doctor in such cases, while 13.4% (n=43) contacted an internist. Only 2.5% (n=8) of the patients indicated that their first correspondent had a different medical specialization (multiple answers possible).

In the group “without intrinsic aortopathy” 264 answers were received. In 88.5% (n=215) of cases, a general practitioner/family doctor was primarily consulted, in 13.2% (n=32) an internist, in 7.0% (n=17) a physician with another medical specialization (multiple answers possible).

In the entire group, according to the study participants, 94.3% of the above-mentioned primary medical care providers were aware that the patient has a CHD. The remaining 5.7% of the providers were unaware of their patients’ CHD or the study participants stated that they did not know whether their primary care provider had knowledge of their existing CHD. There was no significant difference between the groups “at risk/manifest aortopathy” or “without intrinsic aortopathy”.

Basic medical care for CHD-dependent medical problems

In response to the question on the primary contact physician for CHD-specific health problems, 585 answers (multiple answers possible) were received. Even in the case of heart problems, in the group “at risk/manifest aortopathy”, 56.6% (n=181) of the responders were cared for by a general practitioner/family doctor, 18.4% (n=59) by an internist, and 30.0% (n=96) patients primarily by a doctor with a different specialization, including cardiology.

Similarly, in the group “without intrinsic aortopathy” 51.0% (n=124) of the patients primarily consulted a general practitioner/family doctor, 18.5% (n=45) an internist, and 32.9% (n=80) primarily a doctor with a different specialization, including cardiology.

Transfer to an institution specialized in CHD because of a medical problem

Only 32.8% (n=105) of CHD-patients “at risk/manifest aortopathy” reported that a general practitioner/family doctor had referred them to a CHD-specialist in the past because of cardiac problems related to their CHD. Forty-nine-point-four percent (n=158) have never been referred to a CHD-specialist.

Also, in the group “without intrinsic aortopathy”, only 33.7% (n=82) of patients had been referred to a CHD-specialist because of cardiac problems related to their CHD. Even 49.4% (n=120) have never been referred to a CHD-specialist.

Specific counselling needs for advice for patients with CHD with and without aortopathy

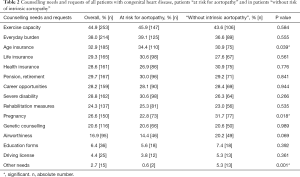

The question in which areas a specific advice is required was answered by the study participants with multiple responses. In all groups, the greatest need for counselling was reported with respect to the ability to perform during physical or sporting activity, to employment and education, to pregnancy and inheritance, to rehabilitation measures, and also to driving license, the ability to travel and to air travel. Moreover, there was also a specific need for information about health insurance, life insurance and retirement (Table 2).

Full table

Patients knowledge about targeted care for ACHD in Germany

All patients were asked about the awareness of certificated facilities for the care of ACHD. Certificated and accredited pediatric cardiologists, adult cardiologists, specialized hospitals and heart centers for ACHD were widely unknown to the majority of all affected patients. There was no significant difference between both groups of “ACHD at risk” and “without risk of intrinsic aortopathy”.

The question of whether the information on specific care structures for ACHD is sufficient was answered by 293 of the 320 participating ACHD “at risk” [91.6%; missing data in 27 (8.4%)]. Only 35.5% (n=104 of 293) participating patients answered positively, another 29.4% (n=86 of 293) were undetermined. In patients “without risk of intrinsic aortopathy” 224 of the 243 participants answered [92.2%; missing data in 19 (7.8%)]. Only 33.0% (n=74 of 224) participating patients answered positively, another 29.5% (n=66 of 224) were undetermined. There was no significant difference between both groups (P=0.812).

Patients knowledge about patient organizations for ACHD in Germany

All patients were asked whether they knew patient organizations for ACHD. This question was answered by all 563 study participants. Similar to targeted medical institutions, patient organizations for ACHD were also widely unknown to the majority of affected patients.

In the group of ACHD “at risk” the question was answered positively by only 38% (n=122) of participating patients, another 10% (n=32) were undetermined. In patients “without risk of intrinsic aortopathy” also only 35% (n=86) participants answered positively, another 12% (n=30) were unsure (Figure 1). There was no significant difference between both groups (P=0.615).

Patient satisfaction in the context of medical care for their CHD

The question concerning satisfaction in the context of medical care for their CHD was answered by 545 study participants (missing data n=18). On a scale of 1–6 (1= very good; 6= unsatisfactory), 311 patients with aortopathy (missing data n=9) rated their medical care on average 1.87 (very good–good). The 234 patients (missing data n=9) without risk gave an average 1.81 (very good–good). There was no significant difference between both groups (P=0.414) (Figure 1).

Discussion

Clinical relevance of the study

This is the first study to explore the medical care provided by primary care physicians (family doctors, general practitioners, or internists) within a large sample of adults with almost all types and severities of CHD and associated risk of having or developing an aortopathy.

Our data indicate that, even in this vulnerable patient group, family doctors and/or general practitioners are in fact the first medical care providers when a general medical problem arises. These first physicians consulted include family doctors and/or general practitioners in 89.4%, internists in 13.4%, and physicians of another specialty in 2.5% (multiple answers permitted). It is remarkable, that almost all of these physicians are aware that their patient has a CHD.

It is however of concern that family doctors and/or general practitioners and internists are also the first consultants to be contacted for CHD-specific health problems. Under these conditions, family doctors or general practitioners are approached in 56.6%, internists in 18.4% and a doctor of another specialty, including cardiology, in at least 30% of cases. This is especially problematic, as many primary care physicians are usually not specifically trained, not experienced in CHD care and unaware of the long-term problems of ACHD. This may even have more severe consequences in view of the ever-growing number of CHD-patients, all of which are chronically ill due to residua and sequelae of the underlying cardiovascular abnormality. Therefore, the spectrum of long-term problems is so widespread that it can only be mastered by CHD-experienced specialists. As described initially, it includes in particular the residual and subsequent conditions specific to the heart defects, including heart failure, cardiac arrhythmias, pulmonary vascular disease/pulmonary hypertension and endocarditis.

In addition, depending on the underlying congenital heart anomaly, aortic alterations become more and more relevant with increasing age. Nevertheless, aortic involvement in CHD remains an often-overlooked condition, although considerable negative effects on morbidity and mortality exist (17).

Aortopathy in genetically determined, syndromic disorders with aortic involvement or in patients with CHD

Aortopathy, defined as progressive dilatation of the proximal aortic root, ascending or descending aorta, is frequently found in genetically determined, syndromic disorders with aortic involvement (e.g., Marfan-syndrome), as well as in the natural or in the postoperative / postinterventional course in CHD (18).

“Aortopathy” is generally characterized by degeneration of the aortic wall layer with aortic medial degeneration, which is associated with aortic dilation or aneurysm formation as well as aortic-ventricular interaction (15).

Aortic medial degeneration is well recognized and reaches its most severe form in genetic determined disorders like Marfan syndrome with annuloaortic ectasia. It is also seen in Loeys-Dietz syndrome, other connective tissue disorders with vascular involvement such as vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, as well as Turner- or Noonan-syndrome (19).

The changes in aortic medial degeneration are inappropriately called “cystic medial necrosis”, although no “cysts” can be found histopathologically. This process is rather characterized by elastic fiber degeneration and fragmentation, non-inflammatory loss of smooth muscle cells, and with accumulation of basophilic ground substances within cell-depleted areas in the media (20).

In other CHD, the above mentioned aortic medial degeneration is qualitatively similar, but seldom quantitatively so pronounced as in Marfan syndrome. Such alterations occur not only in complex but also in simple CHD. In conotruncal anomalies, like Tetralogy of Fallot, pulmonary atresia, truncus arteriosus, the process of dilatation already starts in the prenatal period and the dilatation is flow-related. Besides, aortopathy reflects a common developmental fault that weakens the aortic wall and causes aortic dilatation, decreases aortic elasticity and increases aortic stiffness (14,18,21,22). At least in some congenital heart anomalies, the hypothesis of aortic dilatation has shifted from so called “poststenotic dilatation” to “primary intrinsic” aortopathy.

According to the literature, aortic dilatation and aortic aneurysms occur or develop in many different CHD. Aortopathy is associated particularly with a bicuspid aortic valve, aortic coarctation, conotruncal anomalies such as tetralogy of Fallot, pulmonary atresia with ventricular septal defect, complete transposition of the great arteries, truncus arteriosus communis, double outlet right/left ventricle, or aorto-pulmonary window or aortic arch anomalies. Also, certain patients with univentricular hearts or hypoplastic left heart syndrome after modified Fontan-operation are susceptible (23-26). In addition, aortopathies are frequently seen after any operative treatment involving the aorta, e.g., after arterial switch operation for transposition of the great arteries, or after Ross-operation.

The assumption that the aorta is affected in many CHDs is supported by the large numbers of unselected patients in the present study, where out of the 563 consecutively enrolled ACHD, 320 (56.8%) had a risk of developing aortopathy and/or manifest aortopathy. A proven aortopathy had 57.9% (n=185) of the patients at risk (n=320) and 32.5% of all included patients (n=563). The patients at risk for developing aortopathy and/or manifest aortopathy were predominantly from the group of complex CHD [74 out of 148 (50.0%)], anomalies of the left heart, of the aortic valve or the aorta [124 out of 124 (100.0%)], disorders of the right heart/ anomalies of pulmonary valve or pulmonary artery [75 out of 98 (76.5%)] or, genetic syndromes with aortic involvement [35 out of 35 (100.0%)].

Clinical relevance of aortopathy in patients with CHD

Clinically relevant is the fact, that such an aortopathy may progress and put the affected patients at risk for aortic aneurysm formation and aortic dissection or rupture.

In order to prevent such devastating aortic complications, particularly aortic dissection or rupture, it would be essential to identify high-risk patients at an early stage and, if necessary, to treat them prophylactically or to provide them with appropriate surgical treatment in a timely manner.

Thereby, it is important to know that the decision-making process is strongly dependent on the underlying diagnosis of the CHD or the underlying disease (e.g., Marfan syndrome).

For the medical prophylaxis of the progression of aortic widening, for example, data are available for patients with Marfan syndrome at best, but not for aortopathies in other forms of CHD.

It should also be noted that the indication for prophylactic surgery in adults with acquired, degenerative forms of aortic aneurysm only apply to a limited extent to aortopathies in CHD.

Moreover, aortic dilatation and increased aortic stiffness can induce progredient aortic valve regurgitation, left ventricular hypertrophy, reduced coronary artery flow and left ventricular failure (21,22,27).

The care of patients with aortopathy in patients with CHD

All these facts indicate that ACHD require targeted care and follow-up by experienced specialists.

Starting around the year 2006, in Germany for this reason, pediatric cardiologists and cardiologists who had sufficient experience in the care of ACHD have been certificated. In addition, medical practices, specialist clinics and centers for the care of ACHD were also accredited.

In the meantime, similar to Canada, as of 03/2020 Germany has a nationwide network of more than 348 certified pediatric cardiologists and cardiologists in private practice, 11 certified regional centers and 19 certified supra-regional, tertiary care centers for ACHD. However, as reflected by preliminary data of the VEmaH-study, the problem is that most patients with CHD in Germany do not reach these centers at all (28-30). This fact is consistent with the patients’ statements, that about 50% of the surveyed patients indicated that they have never been referred to a CHD specialist for cardiac problems related to their CHD. It could also be explained, at least in part, by the globally known “loss to follow” phenomenon.

In addition, also the knowledge of patients about the nationwide availability of specialists and centers for the treatment and follow-up of their CHD is completely inadequate. Only 36% of all patients who responded indicated that their information on specific care structures for CHD was sufficient.

Furthermore, only 37% of all responders were aware of the existence of patient organizations for CHD.

Finally, some criticism must be directed towards the study center. Although the German Heart Center Munich is the largest center in Germany for the care of ACHD, many of the patients treated here and many referring physicians are obviously unaware of this fact. Most patients of the Heart Center are in a continuous follow-up for years or decades. For them this is routine. Since they do not perceive deficits in cardiological care, they are not thinking about care structures. This equally applies to the referring physicians.

However, the patient satisfaction with medical follow-up care mainly concerns cardiological aspects. Present study results suggest, that there is an unmet need for further information and consulting. This concerns in particular aspects such as exercise, nutrition, life style, rehabilitation, prevention and socio-medical aspects such as old-age security. This lack of awareness is most likely due to inadequate educational and information work by the Heart Center and needs urgent improvement.

Limitations

The present study engaged a remarkably large sample size of recruited patients with almost all types and severities of CHD. However, current results should be interpreted in the light of certain limitations.

First, only patients who voluntarily agreed to participate were enrolled. The extent to which the patients’ motivation to voluntarily participate remains unknown and may have biased the observations, as patients who voluntarily participate in research surveys differ from those who choose not to participate.

Further, it is possible that the number of patients with manifest aortopathy is even higher than indicated. This may be likely due to the fact that only those patients were classified as “manifest”, in whom an aortopathy was intrinsic or pathological aortic diameters were described in the medical records. The difficulties in interpreting the measured values can be explained by the fact that the aorta can often not be adequately visualized by routine transthoracic echo examinations. In adults, only the first few centimeters of the ascending aorta can often be seen. However, more advanced examinations, such as cardio-MRI, CT or aortography, which allow the entire aorta to be examined, were not routinely performed.

In addition to the absolute size of the aorta, the progression of the aortic diameter over the time would be important for the risk assessment of the affected patients. We have not considered this aspect in our study, as it was a cross-sectional study from the outset and not a longitudinal study.

This study was performed at a tertiary care center for ACHD. Thus, the sample of patients does not represent the typical population of CHD seen by a general practitioner or by a cardiologist. The prevalence of more complex anomalies in these institutions is likely to be higher than either in community-based hospitals or even in departments for cardiology.

Lastly, the presented data derive solely from patients living in Germany. Generalization of the conclusions and transmission to patients living in other countries or different culture groups is debatable.

Conclusions

Although today most patients with CHD survive into adulthood, many of them have relevant residua and sequels, including aortopathy. Even today it is not rarely overlooked, that such aortopathy can cause significant morbidity and mortality, particularly with increasing age. This does not only apply to the rapidly increasing number of adults with complex CHD, but also to simple treated or untreated CHD, which were considered harmless until recently. Therefore, the awareness of patients as well as treating physicians about aortopathies and associated potential risks must be increased to close actual gaps in patient care.

An experienced routine follow-up care by specialized and/or certified physicians or centers is imperative for all patients with CHD, and in particular for those with intrinsic aortopathy or at risk for aortopathy.

Finally, as the presented data derive from people living in Germany, further studies are needed to assess the situation of CHD-patient care in other countries. In a next step further data from other countries might be collected for comparison purposes in order to establish practical international guidelines for the management of the increasing number of ACHD.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the German Heart Foundation (“Deutsche Herzstiftung e.V.”), the patient organization “Herzkind e. V.”, and also the German health care insurance AOK-Bayern for the promotion of ACHD research. This article contains parts of the doctoral thesis of A. Kaemmerer, University of Szeged, Hungary.

Funding: This work was supported by the German Heart Foundation (“Deutsche Herzstiftung e.V.”) (grant number F-30-15), the patient organization “Herzkind e.V.”, Actelion Pharmaceuticals Germany GmbH (grant number MED-2015-495) and the German healthcare insurance AOK-Bayern.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors (Yskert von Kodolitsch, Harald Kaemmerer, Koichiro Niwa) for the series “Current Management Aspects in Adult Congenital Heart Disease (ACHD): Part III” published in Cardiovascular Diagnosis and Therapy. The article has undergone external peer review.

Guideline Checklist: The authors have completed the SURGE guideline checklist. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/cdt-20-359

Data Sharing Statement: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/cdt-20-359

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/cdt-20-359). The series “Current Management Aspects in Adult Congenital Heart Disease (ACHD): Part III” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. CA, PE, SF, ASK, NN, LP, KN, RN, and LS report grants from Deutsche Herzstiftung (Patient organization), grants from Herzkind e.V. (Patient organization), grants from Actelion Deutschland, during the conduct of the study. The other authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The survey has been approved by the institutional review boards of the Technical University Munich (157/16 S) and written informed consent was obtained from all participating patients before the start of documentation.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Mutluer FO, Celiker A. General Concepts in Adult Congenital Heart Disease. Balkan Med J 2018;35:18-29. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van der Linde D, Konings EE, Slager MA, et al. Birth prevalence of congenital heart disease worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:2241-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wren C, O'Sullivan JJ. Survival with congenital heart disease and need for follow up in adult life. Heart 2001;85:438-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Neidenbach R, Niwa K, Oto O, et al. Improving medical care and prevention in adults with congenital heart disease-reflections on a global problem-part I: development of congenital cardiology, epidemiology, clinical aspects, heart failure, cardiac arrhythmia. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther 2018;8:705-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khairy P, Ionescu-Ittu R, Mackie AS, et al. Changing mortality in congenital heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;56:1149-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Erikssen G, Liestøl K, Seem E, et al. Achievements in congenital heart defect surgery: a prospective, 40-year study of 7038 patients. Circulation 2015;131:337-46; discussion 346. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stout KK, Daniels CJ, Aboulhosn JA, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Adults With Congenital Heart Disease: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2019;139:e637-e697. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Neidenbach RC, Lummert E, Vigl M, et al. Non-cardiac comorbidities in adults with inherited and congenital heart disease: report from a single center experience of more than 800 consecutive patients. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther 2018;8:423-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Singh S, Desai R, Fong HK, et al. Extra-cardiac comorbidities or complications in adults with congenital heart disease: a nationwide inpatient experience in the United States. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther 2018;8:814-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lui GK, Rogers IS, Ding VY, et al. Risk Estimates for Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease in Adults With Congenital Heart Disease. Am J Cardiol 2017;119:112-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lui GK, Saidi A, Bhatt AB, et al. Diagnosis and Management of Noncardiac Complications in Adults With Congenital Heart Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017;136:e348-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Perloff JK, Warnes CA. Challenges posed by adults with repaired congenital heart disease. Circulation 2001;103:2637-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Warnes CA. The adult with congenital heart disease: born to be bad? J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;46:1-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Neidenbach R, Niwa K, Oto O, et al. Improving medical care and prevention in adults with congenital heart disease-reflections on a global problem-part II: infective endocarditis, pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary arterial hypertension and aortopathy. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther 2018;8:716-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Niwa K, Kaemmerer H. Aortopathy. Niwa K, Kaemmerer H. editors. Tokyo: Springer Japan, 2017.

- Paruchuri V, Salhab KF, Kuzmik G, et al. Aortic Size Distribution in the General Population: Explaining the Size Paradox in Aortic Dissection. Cardiology 2015;131:265-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- May Khan A, Kim Y. Aortic dilatation and aortopathies in congenital heart disease. Curr Opin Cardiol 2014;29:91-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kuijpers JM, Mulder BJ. Aortopathies in adult congenital heart disease and genetic aortopathy syndromes: management strategies and indications for surgery. Heart 2017;103:952-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- von Kodolitsch Y, Rybczynski M, Vogler M, et al. The role of the multidisciplinary health care team in the management of patients with Marfan syndrome. J Multidiscip Healthc 2016;9:587-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Niwa K, Perloff JK, Bhuta SM, et al. Structural abnormalities of great arterial walls in congenital heart disease: light and electron microscopic analyses. Circulation 2001;103:393-400. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Niwa K. Aortopathy in Congenital Heart Disease in Adults: Aortic Dilatation with Decreased Aortic Elasticity that Impacts Negatively on Left Ventricular Function. Korean Circ J 2013;43:215-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zanjani KS, Niwa K. Aortic dilatation and aortopathy in congenital heart diseases. J Cardiol 2013;61:16-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Niwa K. Aortic dilatation in complex congenital heart disease. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther 2018;8:725-38. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Niwa K. Aortic root dilatation in tetralogy of Fallot long-term after repair--histology of the aorta in tetralogy of Fallot: evidence of intrinsic aortopathy. Int J Cardiol 2005;103:117-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zaidi AN, Kay WA, Daniels CJ, et al. Aortopathy in Adults with Congenital Heart Disease. In: da Cruz E, Ivy D, Jaggers J. editors. Pediatric and Congenital Cardiology, Cardiac Surgery and Intensive Care. London: Springer, 2014:2651-68.

- Francois K. Aortopathy associated with congenital heart disease: A current literature review. Ann Pediatr Cardiol 2015;8:25-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Senzaki H, Iwamoto Y, Ishido H, et al. Arterial haemodynamics in patients after repair of tetralogy of Fallot: influence on left ventricular after load and aortic dilatation. Heart 2008;94:70-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Neidenbach R, Kaemmerer H, Pieper L, et al. Striking Supply Gap in Adults with Congenital Heart Disease? Dtsch Med Wochenschr 2017;142:301-3. [PubMed]

- Neidenbach R, Pieper L, Freilinger S, et al. Adults with congenital heart disease: lack of specific disease related medical health care from the patients point of view. Eur Heart J 2018;39:111.

- Neidenbach R, Pieper L. Adults with congenital heart disease: lack of specific disease related medical health care from the general practitioners view. Eur Heart J 2018;39:112.