Pregnancy outcomes in patients with structural heart disease: a single center experience

Introduction

In women, pregnancy is a period of relatively drastic hemodynamic changes in a short period of time (1,2). These gradual hemodynamic changes have a significant effect on the cardiovascular system. However, most women of childbearing age are relatively young, and in the absence of cardiovascular disease can adapt well to these sudden hemodynamic changes. However, during pregnancy the cardiac output increases, and changes in hormones and in the autonomic nervous system can lead to heart failure or arrhythmia (3-7). However, not much is known about the pregnancy outcomes of pregnancy in patients with congenital heart disease (8-16). Sejong general hospital is the secondary referral center for cardiovascular disease, and many patients with congenital heart disease are referred here. This study was conducted to analyze the outcomes of pregnancy in adult congenital heart disease or specific structural heart disease.

We present the study in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/cdt-20-786).

Methods

Study subjects and period

From January 2007 to December 2016, we reviewed medical records of all pregnant women with congenital heart disease or specific structural heart disease among women who received obstetric care at the Sejong General Hospital. Patients having arrhythmia, but without congenital heart disease or specific structural heart disease were excluded from this study. We also excluded cases of hypertension and peripartum cardiomyopathy in the absence of any structural diseases of the heart.

Collected data

The patient’s data of underling disease, history of pervious surgery and treatment, current medications, and vital symptoms and signs were retrieved through the medical records. Since the echocardiograms had been performed by different physicians, two pediatric cardiologists (EY Choi, JY Kim) re-analyzed the echocardiograms to re-evaluate the degree of regurgitation and stenosis of the cardiac valves, and the function of the ventricles. To evaluate the hemodynamic status before pregnancy, echocardiographic images performed within 2 years before pregnancy were used. Right ventricular (RV) dysfunction was defined as fractional area shortening (FAC) less than 35% and left ventricular (LV) dysfunction as less than 55% of ejection fraction (EF). The degree of valvular regurgitation and stenosis were classified as mild, moderate, and severe; moderate and severe lesions were considered as hemodynamically significant. Data of the gestational age, birth weight, Apgar score, and presence of the heart disease in the babies were also retrieved from the medical records.

Definition of events

In cases of maternal cardiac death, symptomatic arrhythmia during pregnancy, deterioration of New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class in two or more grades, pulmonary edema, stroke or cerebrovascular accident, and ventricular dysfunction in the postpartum period were defined as cardiac events. Ventricular dysfunction in the postpartum period was defined as a 10% or more reduction in LV EF or 10% or more reduction in RV FAC than pre-pregnancy exams within 6 months of delivery.

Maternal pregnancy induced hypertension, postpartum hemorrhage, non-cardiac death, and pre-eclampsia were defined as obstetric events.

Preterm infants less than 37 weeks of gestation, birth weight less than 10th percentile of that for the gestational age, fetal death, neonatal death, Apgar score less than 5 and congenital heart disease in neonates with hemodynamic significance were considered as neonatal events.

Statistical analysis

Chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test were performed to confirm the association of cardiac, obstetric and neonatal events with the hemodynamic status of each mother. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical statement

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national guidelines on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). The study has been approved by the institutional committees (No. 1753), and the informed consents were waived due to the retrospective nature.

Results

During the study period, 105 pregnancies were observed in 80 women with structural heart disease. Among these, 103 pregnancies were observed in 79 patients, while 2 pregnancies lost to follow-up. Since the same women was pregnant several times, the number of pregnancy was indicated as the number of events. Of the 103 pregnancy events, 55 were primiparous and 48 were multiparous.

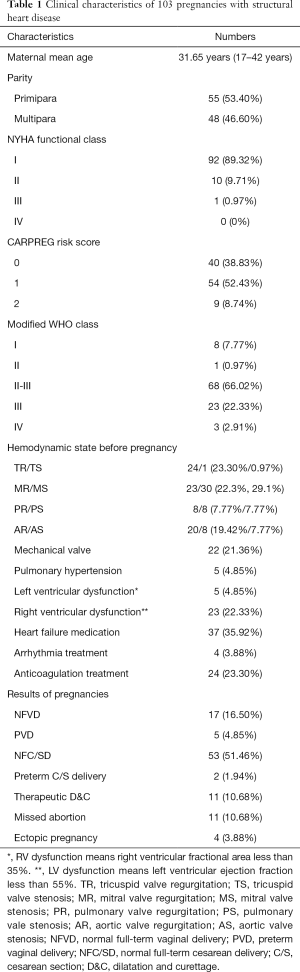

In the echocardiography performed before pregnancy, the most common hemodynamically significant valve lesions were mitral valve stenosis (MS) at 30 events (29.13%). Tricuspid valve regurgitation (TR) was present in 24 events (23.30%) and mitral valve regurgitation (MR) in 23 events (22.30%). A mechanical valve was present in 22 events (21.36%) and pulmonary arterial hypertension was present in 5 events (4.85%). Of the 15 patients with mechanical valves, 12 had mechanical mitral valve, 2 had mechanical aortic valve, and one had mechanical aortic valve and mitral valve. Table 1 shows the clinical characteristics of the pregnant women and the NYHA functional class, which is commonly used for functional classification of cardiac patients, and the cardiac disease in pregnancy (CARPREG) risk score and modified WHO class, which are used to assess the risk in pregnant women. In the pre-pregnancy state, 5 patients had LV dysfunction: 2 of dilated cardiomyopathy, congenital MR without surgery, postoperative congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries and postoperative Marfan syndrome. On the other hand, there were 21 patients with RV dysfunction. There were 5 repaired atrial septal defect (ASD) patients, 4 repaired ventricular septal defect (VSD), 2 repaired tetralogy of Fallot (TOF), 2 repaired double outlet right ventricle (DORV), and 2 unrepaired ASD. In addition, there were 1 patient each repaired Ebstein’s anomaly, unrepaired Marfan, rheumatic MS post percutaneous mitral valvuloplasty, repaired congenital MR, repaired congenital aortic valve regurgitation (AR), and repaired pulmonary valve stenosis (PS). Six patients had hemodynamically significant arrhythmia before pregnancy. There underlying disease were rheumatic MS in 3 patients, VSD in 2 patients, and 1 hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCMP). All of them had already undergone corrective surgery, and left atrial enlargement was severe due to the remaining valve lesions.

Full table

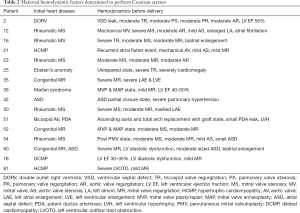

Of 103 pregnancies, 77 resulted in delivery. There were 4 fetal death in utero (FDIU), 1 pair of natural twins, and 1 fetus had severe fetal hydrops which required induced delivery for therapeutic termination. Thus, 73 live births were recorded. Of these, 40 were boys and 33 girls, and the average weight was 3.05 kg (range, 1.96–3.85 kg). There were 55 Cesarean section (C/S) deliveries among the 77 deliveries; thus, the proportion of surgery was high. Of these, 16 cases were delivered under C/S considering the maternal cardiac risk rather than an obstetrical indication. In our hospital, the obstetric indications for choosing a C/S are previous C/S history, failure to progress during labor, fetal mal-presentation, abnormal placentation, etc. The pre-partum cardiac risk factors of mothers who choose C/S by medical staff were very diverse, and are presented in Table 2. The 26 pregnancies did not last. Among them, 11 were spontaneous abortions, 4 were abortions due to tubal pregnancy, and 11 abortions were performed considering the maternal hemodynamic condition.

Full table

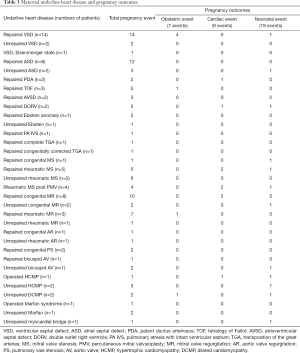

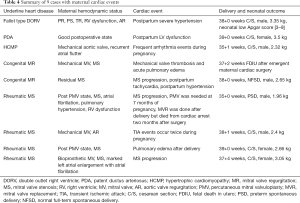

Table 3 shows the frequency of maternal underlying heart disease and pregnancy outcomes. There were 9 maternal cardiac events, 7 obstetric events, and 19 neonatal events. In 1 case, an obstetric event and neonatal event occurred simultaneously. In 5 cases, both cardiac and neonatal events were seen. Thus, 29 out of 103 pregnancy events had one or more obstetric, cardiac, and neonatal events, resulting in a very high rate of complications at 28.16%. Among the obstetric events, ectopic pregnancy was the most common in 4 cases. Pre-eclampsia, pregnancy induced hypertension and postpartum bleeding occurred in 1 case each. Neonatal events included 6 preterm infants, 6 small for gestational age infants, 2 infants with low Apgar scores less than 5, and 4 intrauterine fetal deaths. Surgical correction for VSD and atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD) was required in 1 infant each. 6 of 9 patients with cardiac events had hemodynamic problems of the mitral valve. In 1 case among the 9 cardiac events, intrauterine fetal death occurred during the maternal cardiac surgery under cardiopulmonary bypass. Another mother underwent induction of labor and maternal heart surgery; however, she did not recover and died about 2 months later. Table 4 summarizes the 9 cases in which cardiac events occurred.

Full table

Full table

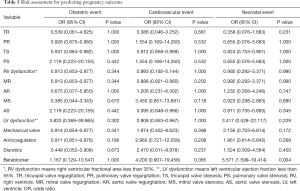

Chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact test were performed to predict obstetric, cardiovascular and neonatal events. The results are shown in Table 5. The risk of neonatal event was 5.571 times higher when the mother was administered a beta-blocker before pregnancy. However, no statistically significant correlation was found between other hemodynamic characteristics and pregnancy outcomes.

Full table

Discussion

Of the 103 pregnancies included in this study, 29 (28.16%) had poor pregnancy-related outcomes. In this study, 8.34% (9/103) of the cases had maternal cardiac events. Previously published studies had reported that the incidence of maternal cardiac events is 10% to 30% (8,13,16). The reason for the lower maternal cardiac events compared to other studies is that the patients with severe heart disease such as Fontan or systemic right ventricles were not included.

Among the 29 adverse outcomes, there were 23 cases of NYHA functional class I, 14 cases of CARPREG risk score 0, and 8 cases of modified WHO class I. These results suggest that it is difficult to accurately predict the risk factor of poor pregnancy outcome in patients with structural heart disease, by following the general classification that is currently used. Although pregnancy is not a medical condition, it is challenging for women with structural or functional abnormalities of the heart, since gradual hemodynamic changes occur in a short period during this phase. In the case of heart disease, various degrees of valvular stenosis, valvular regurgitation, arrhythmia, or ventricular dysfunction might remain after surgery. Therefore, adequate preparedness before pregnancy is very important for anticipated complications (6,8,13,14). Unfortunately, in this study, there were only 47 cases (45.63%) who underwent prenatal consultations with cardiologists regarding the risks related to pregnancy. In the absence of antenatal counseling for pregnancy, we had to perform therapeutic abortion in 11 cases, following consultation and counseling about contraception. There was no medical event associated with therapeutic abortion. However, counselling about the appropriate method of contraception is important for the health of the patient (12,13,15-17).

In this study, we tried to investigate the relationship between specific hemodynamic impairment and obstetric, cardiovascular and neonatal events. However, as shown in Table 5, it was difficult to find a clear association except for the increased risk of neonatal events due to maternal intake of beta-blockers. It is known that intake of beta-blockers during pregnancy can cause uteroplacental insufficiency and inhibit fetal growth (18). Among the patients included in the study, beta blocker was taken from before pregnancy in 13 pregnancy events, including carvedilol in 5 patients, atenolol in 4 patients, and bisoprolol in 4 patients. The increase in heart rate and stroke volume during pregnancy increases the burden of the heart. However, in during pregnancy, there is a decrease in the heart burden, due to the decrease in the vascular resistance of the body. Because we do not have many patients, it is difficult to make hasty generalizations. However, most maternal cardiac events occurred mainly in the presence of mitral valve lesions, suggesting that the right ventricle is relatively well-adapted to the volume overload during pregnancy. Table 4 shows 9 cases of cardiac event, of which 5 cases had significant MS before pregnancy. Of course, 1 surgically ligated patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) patient with no residual hemodynamic problems was included, but the underlying disease was mitral valve lesions in 6 cases.

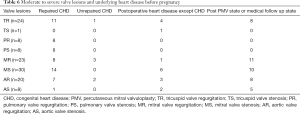

The number of adults with congenital heart disease is steadily increasing, due to an improvement in the surgical outcomes of congenital heart disease. As a result, the number of women with congenital heart disease reaching fertility is also increasing (1,12,14-17,19-22). There have been some studies on pregnancy outcomes in such patients with various hemodynamic impairments and receiving various types of medical care. However, congenital heart disease or structural heart disease involves a wide spectrum of conditions, and the hemodynamic status after correction varies widely among individuals. In a total of 72 pregnancy events, at least one moderate to severe valve reflux or stenosis was observed before pregnancy, and details are provided in Table 6. Among them, 44 events were patients with repaired congenital heart disease. Hence, classifying the patient’s hemodynamic status is very difficult. Unfortunately, in this study, it was not possible to conclude how much specific valve lesions affect the pregnancy outcome, but it may be possible if data from more patients are accumulated.

Full table

Of the 103 pregnancy events, there were 11 events of missed abortions and 11 events were performed therapeutic abortion through maternal risk assessment after pregnancy. The main reasons were uncontrolled arrhythmia, severe valve lesions, and severe pulmonary hypertension, in the case of waiting for cardiac surgery, but 5 cases were due to the increased fetal risk due to uncontrolled anticoagulation. Of these, there was only one case of receiving enough prenatal counseling. Unfortunately, out of 103 events, only 47 events (45.63%) received counseling about cardiovascular disease and associated risk factor before pregnancy. In the future, the authors hope that more active prenatal counseling and preparation can improve pregnancy outcome and reduce the risk of maternal health. If there were enough counseling about the risks that mothers may face associated pregnancy before pregnancy, as well as counseling and education about contraceptive therapy, we think they could have reduced the number of abortions and managed more safely. We believe that careful management of pregnant women with structural heart disease can be achieved by actively involving the cardiologists in the planning of pregnancy, ante-natal care, and delivery.

Study limitations

This study was conducted at secondary center where about 500 congenital heart surgeries are performed annually. Since our hospital is not a tertiary referral center, there is a limitation in inferencing the data, because all women undergoing open heart surgery and follow-up observation at our hospital, do not receive obstetric care at our institution. Moreover, there were no high-risk patients with single ventricle or systemic right ventricle in this study. In addition, it includes not only congenital heart disease but also rheumatic valvular heart disease or cardiomyopathy, which may confuse the interpretation of the results. Also, because the number of patients included in the study was small, it was impossible to assess the risk according to the patients’ hemodynamic status.

Conclusions

Overall complications associated with pregnancy in women with structural heart disease are very high, 28.16%. However, it is hoped that maternal and neonatal outcomes will be improved through careful monitoring and preparedness for anticipated complications.

Acknowledgments

We really appreciated Yeonok Lee (PhD. in statisitcs) who helped in analyzing the data. And we would like to thank Editage (www.editage.co.kr) for English language editing. In the 62nd session of the Korean Society of Cardiology, part of this paper was presented.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors presented the study in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/cdt-20-786

Data Sharing Statement: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/cdt-20-786

Peer Review File: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/cdt-20-786

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/cdt-20-786). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national guidelines on human experiments and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). The study has been approved by the institutional committees (No. 1753), and informed consents were waved due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Bhatt AB, DeFaria Yeh D. Pregnancy and adult congenital heart disease. Cardiol Clin 2015;33:611-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Greutmann M, Pieper PG. Pregnancy in women with congenital heart disease. Eur Heart J 2015;36:2491-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lu CW, Wu MH, Wang JK, et al. Preconception counseling for women with congenital heart disease. Acta Cardiol Sin 2015;31:500-6. [PubMed]

- Wald RM, Sermer M, Colman JM. Pregnancy in young women with congenital heart disease: Lesion-specific considerations. Paediatr Child Health 2011;16:e33-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Warnes CA. Pregnancy and delivery in women with congenital heart disease. Circ J 2015;79:1416-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Uebing A, Steer PJ, Yentis SM, et al. Pregnancy and congenital heart disease. BMJ 2006;332:401-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Harris IS. Management of pregnancy in patients with congenital heart disease. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2011;53:305-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Franklin WJ, Gandhi M. Congenital heart disease in pregnancy. Cardiol Clin 2012;30:383-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ruys TP, Cormette J, Roos-Hesselink JW. Pregnancy and delivery in cardiac disease. J Cardiol 2013;61:107-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Connolly HM. Pregnancy in women with congenital heart disease. Curr Cardiol Rep 2005;7:305-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khan A, Kim YY. Pregnancy in complex CHD: focus on patients with Fontan circulation and patients with a systemic right ventricle. Cardiol Young 2015;25:1608-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hayward RM, Foster E, Tseng ZH. Maternal and fetal outcomes of admission for delivery in women with congenital heart disease. JAMA cardiol 2017;2:664-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Siu SC, Sermer M, Colman JM, et al. Prospective multicenter study of pregnancy outcomes in women with heart disease. Circulation 2001;104:515-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rao S, Ginns JN. Adult congenital heart disease and pregnancy. Semin Perinatol 2014;38:260-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Simpson LL. Maternal cardiac disease: update for the clinician. Obstet Gynecol 2012;119:345-59. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thakkar AN, Chinnadurai P, Lin CH. Adult congenital heart disease: magnitude of the problem. Curr Opin Cardiol 2017;32:467-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Canobbio MM, Warnes CA, Aboulhosn J, et al. Management of pregnancy in patients with complex congenital heart disease: A scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American heart association. Circulation 2017;135:e50-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pieper PG, Balci A, Aamoudse JG, et al. Uteroplacental blood flow, cardiac function, and pregnancy outcome in women with congenital heart disease. Circulation 2013;128:2478-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Song YB, Park SW, Kim JH, et al. Outcomes of pregnancy in women with congenital heart disease: a single center experience in Korea. J Korean Med Sci 2008;23:808-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ntiloudi D, Zegkos T, Bazmpani MA, et al. Pregnancy outcome in women with congenital heart disease: A single-center experience. Hellenic J Cardiol 2018;59:155-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khairy P, Ouyang DW, Femandes SM. el al. Pregnancy outcomes in women with congenital heart disease. Circulation 2006;113:517-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ouyang DW, Khairy P, Fernandes SM, et al. Obstetric outcomes in pregnant women with congenital heart disease. Int J Cardiol 2010;144:195-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]