Median arcuate ligament syndrome (Dunbar syndrome)

IntroductionOther Section

- Introduction

- Clinical presentation

- Diagnosis

- Management

- Conclusions

- Acknowledgments

- Footnote

- References

Median arcuate ligament syndrome (MALS) also called as Dunbar syndrome is a vascular compression syndrome. It is technically known as celiac artery compression syndrome resulting from the compression of celiac axis by median arcuate ligament and diaphragmatic crura. First described anatomically in 1917 by Lipshutz (1), who performed cadaveric dissections and showed the overlapping of celiac artery by the diaphragmatic crura leading to compression. Harjola (2) reported symptomatic relief of postprandial epigastric pain in a 57-year-old man after surgical decompression of the celiac artery from a fibrosis of celiac ganglion. In 1965, Dunbar et al. reported a case series involving surgical management of MALS (3).

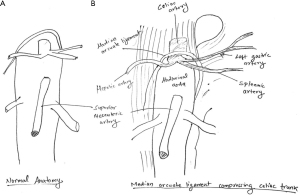

The celiac axis generally arises from the abdominal aorta usually between T11 to L1, however there is wide variation of its origin (4). The diaphragmatic crura arises form L1–L4 where anterior longitudinal ligament meets at anterior and superior aspect of celiac artery. The Median arcuate ligament consists of a band of fibrous tissue connecting anteriorly the diaphragmatic crura surrounding the aortic hiatus. The higher origin of celiac artery or lower insertion of diaphragmatic crura are likely to lead to MALS (Figure 1) (5). Sometimes median arcuate ligament crosses the lower abdominal aorta causing compression (6). Very often compression is increased during expiration due to upward movement of vasculature including the celiac axis. Compression can be due to thick, fibrous tissue or thin bands at or near the origin of celiac artery (7).

Clinical presentationOther Section

- Introduction

- Clinical presentation

- Diagnosis

- Management

- Conclusions

- Acknowledgments

- Footnote

- References

MALS is a rare and is more common in females having thin body habitus in the 3rd to 5th decade of life (8). The syndrome consists of postprandial symptoms including pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and unexplained weight loss (9,10). Cusati et al. (11) in a study consisting of 36 patients with MALS to evaluate the symptoms. This included abdominal pain (94%), postprandial abdominal pain (80%), weight loss (50%), bloating (39%), nausea and vomiting (55.6%), and abdominal pain triggered by exercise (8%).

Park et al. (12) in their study of 400 celiac artery angiograms in asymptomatic patients for chemoembolization of hepatic tumors, found that 7.3% of these patients had significant celiac stenosis, defined as >50% stenosis and > a 10-mmHg pressure gradient (12). Derrick et al. reported that celiac artery stenosis presented with post prandial abdominal pain (13).

DiagnosisOther Section

- Introduction

- Clinical presentation

- Diagnosis

- Management

- Conclusions

- Acknowledgments

- Footnote

- References

MALS is usually a diagnosis of exclusion. It generally mimics abdominal disorders. Duplex ultrasonography can be a good initial screening tool for celiac artery compression due to its lack of ionizing radiation and contrast need. However, it is operator dependent and needs experienced operator to evaluate and show the changes. In addition, it is limited by body habitus and overlying bowel gas. It can show the post stenotic dilatation and elevated velocities exaggerated during expiration (14,15). Computed tomography angiogram (CTA) helps in the diagnosis allowing three-dimensional visualization of compressed celiac artery. CTA has high resolution and can show changes like post stenotic dilatation (Figure 2A,2B); however, it involves ionizing radiation and needs contrast which can be a limitation in patients with renal dysfunction. Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) can an alternative modality for those patients who have allergy to intravenous contrast agents. Additionally, MRA does not use ionizing radiation. Conventional angiography is the gold standard to show dynamic compression. Sometimes lateral mesenteric angiogram can be used for best evaluation of anatomy and dynamic changes (Figure 2C-2F). Cephalic movement of the celiac axis during expiration can reveal celiac artery compression and post stenotic dilatation on expiration. Angiography with breathing maneuvers can be very helpful for diagnosis. Celiac artery compression can be noted during expiration with associated collaterals developed due to the compression, usually from the superior mesenteric artery (SMA). Angiogram can be also used for the evaluation of the patients who develop symptoms postoperatively (10).

ManagementOther Section

- Introduction

- Clinical presentation

- Diagnosis

- Management

- Conclusions

- Acknowledgments

- Footnote

- References

The treatment of MALS aims at decompression of celiac artery to establish adequate blood flow and pain management by neurolysis. Surgery is the definitive management. Historically, open decompression used to be the first choice, where the surgeon will dissect and separate the diaphragmatic crura from celiac axis. The neuropathic pain of MALS can be addressed with removal or ablation of ganglion and

There is role of PTA in post-surgical recurrence. PTA is useful as an adjuvant in the patients with residual symptoms after surgery with addition of balloon expandable stents (18). Recent trends include robotic assisted release of compression and celiac neurolysis (19).

ConclusionsOther Section

- Introduction

- Clinical presentation

- Diagnosis

- Management

- Conclusions

- Acknowledgments

- Footnote

- References

MALS is a rare entity and a diagnosis of exclusion. The diagnosis is difficult and needs a high grade of suspicion with supportive imaging findings. The treatment is aimed at relieving the symptoms with open or laparoscopic surgery with PTA and stenting as adjuvant to robotic ligament release and celiac neurolysis. However, further definitive studies are needed to address the pathophysiology, better diagnose and devise minimally invasive treatment for this entity.

AcknowledgmentsOther Section

- Introduction

- Clinical presentation

- Diagnosis

- Management

- Conclusions

- Acknowledgments

- Footnote

- References

Funding: None.

FootnoteOther Section

- Introduction

- Clinical presentation

- Diagnosis

- Management

- Conclusions

- Acknowledgments

- Footnote

- References

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors (Sanjeeva Kalva and Marcin Kolber) for the series “Compressive Vascular Syndromes” published in Cardiovascular Diagnosis and Therapy. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: Both authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/cdt-20-846). The series “Compressive Vascular Syndromes” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

ReferencesOther Section

- Introduction

- Clinical presentation

- Diagnosis

- Management

- Conclusions

- Acknowledgments

- Footnote

- References

- Lipshutz B. A composite study of the coeliac axis artery. Ann Surg 1917;65:159-69. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Harjola PT. A rare obstruction of the coeliac artery. report of a case. Ann Chir Gynaecol Fenn 1963;52:547-50. [PubMed]

- Dunbar JD, Molnar W, Beman FF, et al. Compression of the celiac trunk and abdominal angina. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med 1965;95:731-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Loukas M, Pinyard J, Vaid S, et al. Clinical anatomy of celiac artery compression syndrome: a review. Clin Anat 2007;20:612-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Horton KM, Talamini MA, Fishman EK. Median arcuate ligament syndrome: evaluation with CT angiography. Radiographics 2005;25:1177-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Reuter SR, Bernstein EF. The anatomic basis for respiratory variation in median arcuate ligament compression of the celiac artery. Surgery 1973;73:381-5. [PubMed]

- Brandt LJ, Boley SJ. Celiac axis compression syndrome. A critical review. Am J Dig Dis 1978;23:633-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Trinidad-Hernandez M, Keith P, Habib I, et al. Reversible gastroparesis: functional documentation of celiac axis compression syndrome and postoperative improvement. Am Surg 2006;72:339-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gloviczki P, Duncan AA. Treatment of celiac artery compression syndrome: does it really exist? Perspect Vasc Surg Endovasc Ther 2007;19:259-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Duffy AJ, Panait L, Eisenberg D, et al. Management of median arcuate ligament syndrome: a new paradigm. Ann Vasc Surg 2009;23:778-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cusati DA, Noel AA, Gloviczki P, et al. Median arcuate ligament syndrome: a 20-year experience of surgical treatment. Philadelphia: 60th Annual Meeting of the Society for Vascular Surgery, 2006.

- Park CM, Chung JW, Kim HB, et al. Celiac axis stenosis: incidence and etiologies in asymptomatic individuals. Korean J Radiol 2001;2:8-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Derrick JR, Pollard HS, Moore RM. The pattern of arteriosclerotic narrowing of the celiac and superior mesenteric arteries. Ann Surg 1959;149:684-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Scholbach T. Celiac artery compression syndrome in children, adolescents, and young adults: clinical and color duplex sonographic features in a series of 59 cases. J Ultrasound Med 2006;25:299-305. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Skeik N, Cooper LT, Duncan AA, et al. Median arcuate ligament syndrome: a nonvascular, vascular diagnosis. Vasc Endovascular Surg 2011;45:433-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Takach TJ, Livesay JJ, Reul GJ Jr, et al. Celiac compression syndrome: tailored therapy based on intraoperative findings. J Am Coll Surg 1996;183:606-10. Erratum in: J Am Coll Surg 1997;184:439. [PubMed]

- Loffeld RJ, Overtoom HA, Rauwerda JA. The celiac axis compression syndrome. Report of 5 cases. Digestion 1995;56:534-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Columbo JA, Trus T, Nolan B, et al. Contemporary management of median arcuate ligament syndrome provides early symptom improvement. J Vasc Surg 2015;62:151-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jaik NP, Stawicki SP, Weger NS, et al. Celiac artery compression syndrome: successful utilization of robotic-assisted laparoscopic approach. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 2007;16:93-6. [PubMed]